The events described here took place in 1941-early 1942 when the 19th Army was operating in the Kandalaksha sector of the Karelian Front.

Ivan Kobec, 1941 |

Episode 1

.My military life, from the first days of the war, began with taking command of the "Hunters" platoon of the 1st Battalion, 596th Rifle Reg., which was formed after the first two weeks into the war. The platoon was constantly in action, pursuing various objectives, but its primary function was the reconnaissance for the battalion and the regiment. In the first months of the war, our battalion was given specific sectors, beginning with the Kuolayarvi area on the state border, then Kajrala, then north of Alakurtti. Only when the Verman defense line was established, we began operating within the regiment.

In mid-August, because of the difficult situation in the area east of Kajrala, units of the 104th and 122nd Rifle Divisions received orders to fall back and retreated to the transitory defense line near Alakurtti. Our 1st Battalion left Ungojvanselka Mt. and reached Ienikuvaara Mt. at the end of the day. At that same time, we lost communication with the regiment commander. The battalion was under command of recently assigned First Lieutenant Pavel Gavrilovich Danilov, a weathered, reasonable and meticulous officer. A little later, he became the commander of the 596th Rifle Reg.

Under the circumstances, we desperately needed to establish communication with the regiment's command and receive objectives for further actions. While on the top of Ienikuvaara Mt., I was ordered to locate the regiment's command center by morning and clarify the battalion's further objectives. I was shown the direction on the map in which to search for the regiment's command. This was not an easy task because the enemy units already operated in the area and we could make sudden contact anytime. There was no time for contemplation and I had to set out on my mission as soon as possible. Having gathered my men, whom there were 12, I made the mission plan clear to them. I must say that the men were exhausted by preceding fights and suffered from malnutrition - the adversary took a part of the road Alakurtti-Kajrala and interrupted our supplies.

|

|

Leaving on the mission, we warned our guys that we'll be coming back the same route and started our descent along a clearing in the woods. The night was dark and quiet, we proceeded slowly and carefully. We had to stop often, pay attention to every rattle and rustle. When hearing curt German phrases, we veered aside and continued moving in the right direction. My scouts kept nearby so that quiet commands could be heard by everyone. We carried on that way until dawn. In the early morning, we came across the regiment's men - those were signalers, three of them. When I asked where was the headquarters, they pointed the direction and told me to take the right turn after 300-400 meters. Luckily, we made it very quick to the staff location where I went to see the regiment commander. The meeting was beyond description as they had been much worried about the absence of communication with the 1st Battalion for so long. While they prepared the documentation for the battalion commander, we rested from the night trek. When the package was ready, we took off. We hurried lest we be too late, and there wasn't much time. It was easier to walk in the morning, yet it was more dangerous. The sun was up and it was nice to feel the warmth of the sunshine. The nights beyond the Arctic Circle at that time of year can be cool. While walking and crossing patches of ample berries, we grabbed handfuls and ravenously put them in our mouths to quench the hunger.

|

A "tongue" is captured. Karelian front. (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

We were approaching the battalion's location - only 300-400 meters of thinly wooded ground was left to cross. We were filled with joy and satisfaction over the mission completed on time. All of a sudden, bursts of a submachine gun roared ahead of us and I saw one of the front scouts running to me. He reported that there were Germans in 30-40 meters ahead of us. Our front group was shot at and one of the scouts was killed. I was so overwhelmed by this, one can hardly imagine. I could expect a sudden encounter with the Germans anywhere else but here, where our battalion just was.

We had no idea of the enemy numbers nor their positions. One thing was clear, they turned up here during the night, while we were gone. In such a situation, one needs to act quickly and unfalteringly, there's no time to think long. Intuitively, I decided to charge at once, break through the enemy lines and force our way toward the battalion as quickly as possible. There were no other options, we had no time for any other course of action. Only several seconds passed; I looked up at my scouts and saw them reading my mind - we rushed into attack. Everybody dashed in a some kind of frenzy, shouting "Hurrah!", throwing hand grenades and firing on the run, soon we were past their frontline. Everything happed so quickly that the adversary could not even understand what was happening and why there was an attack from their behind. And we had been in their rear, for their frontline was facing our battalion. And then, something totally unbelievable and unpredictable ensued: from the top of the mountain, where the battalion was, machine gun fire began, so powerful as we couldn't raise our heads. We just found ourselves in a crossfire.

Our guys pounded from the top, the enemy - from below. For a moment, the Germans slowed down. They may have been utterly confused, why the Russians are shooting at their own. In this horrible situation, something had to be done as I started losing people. From the bottom of my lungs, I yelled to our machine gunners to cease fire. It is still before my eyes, as one of my scouts, a brawny, tall Muscovite named Volkov, who was by me, suddenly moaned and whispered that he was wounded in the hip. I ordered him to stay put and lower himself as much as possible, - that same moment I saw blood trickling from his left temple. Suddenly, the fire stopped, they must have heard me yelling and that made things easier. Immediately, I command the scouts "Charge ahead!" Some crawling, some crouching, we began moving toward the battalion. The bushes helped us part with the pursuing enemy. I was still extremely shocked by these events but gradually recovered and reported to the battalion commander. It turned out, the thing I feared most happened. The unit posted at the entry point was changed with another, and the replacement was not told about our return. As a result, three of my men were killed and two wounded. In that fight, one bullet made a hole in my cap and another torn apart the half-belt on the back of my greatcoat. Indeed, I was pressing to the ground so hard that had I been only a centimeter higher, I would have been dead.

We buried our dead comrades at the top of the mountain and put three large rocks on their graves.

Upon our return, the enemy was suppressed with strong mortar fire. The battalion quickly assembled and operated on orders from the regiment commander. My platoon and I remained at the mountain foot to catch up on rest after the last night's trip. Everybody quickly fell asleep. Half an hour later we rose and saw a wide track left in dewy grass by the leaving battalion. We followed the trail toward the Nurmijoki river until it was time to cross the road already controlled by the adversary.

The sky was cloudless, the sun in the high noon.

Episode 2.

In early September 1941, after heavy fights on the Kajrala and Alakurtti lines, the 122nd and 104th divisions retreated to the Verman defense line and stopped the enemy; the Germans never got past this point. The 596th Rifle Regiment was first deployed to the east of the Sredni Verman river but didn't remain there long. In the second half of September, the regiment took position on Lake Verman and the Nizhni Verman river, its left flank touching Lake Tolvand.

Both our forces and the adversary continued fortifying their positions. Our command needed information on the enemy, its formation and numbers on the opposite side. The regiment staff commander, Captain N.M. Butov, called me in and read out the mission objective: as night fell, we were to infiltrate the enemy lines north of Lake Nizhni Verman and obtain a "talkie" - an enemy's serviceman to be brought back and interrogated. There was very little time for preparations; in whatever time I had, I could only make clear the mission to my scouts, pick people and equip them. Only nine men were selected for the mission. A group this small could easier penetrate the enemy lines and remain undetected while operating. There were very experienced scouts in the group, those who had done many similar missions before. These were Sgt. Semenov, Priv. Ozerov, etc. Though there were some inexperienced people, too, selected from the regiment's new arrivals. I remember how everyone was yearning for rest, catching up on sleep after our routine duties. In this case, we weren't given any specifics as far as the subject goes, we simply had to go and seek. This made the mission more complicated as we had to search in the unknown terrain, knowing nothing the adversary. Their front line already had minefields and barbed-wire obstacles. The terrain was wooded, with large boulders, up to 1.5 m high, scattered here and there. Right before the frontline, there was the shallow Sredni Verman river, 8-10 meters wide. As the night fell, we took off. As we approached the river, we saw several logs thrown across by somebody. That's where the unfortunate event took place which caused a delay. When crossing the river over the logs, Private Rybin slipped and fell into the water. At first, I wanted to send him back but he begged to come along. I gave in and, after a short pause, we crawled past their outposts and headed deep inside. Lest nobody get lost in the dark, we moved very slowly, not in a single file like in the daytime, but in a compact pack, so that everybody could hear my hushed commands.

In 500-600 meters after the frontline, we suddenly hit a barbed-wire fence and set off the garlands of tin cans hanging on the wire; a machine gun burst immediately followed in our direction and we even got lit by it. The group leapt aside and we were lucky that nobody was lost in the darkness. Fearing pursuit, we ran to a safer place. The incident made me think hard - we were detected and shot at and the enemy was now alarmed. Going back was impossible. Hence, the only option was to remain where we were until dawn and, by observing and moving deeper inside, identify a target. During the following night, we were to attack and acquire the "talkie". The rest of the group supported me.

It was a quiet and bright morning, short bursts and single shots could be heard from the frontline. We hid in a small brush on top of a butte. The sound of an axe and somebody speaking German was heard from 200-300 meters away. I made myself comfortable and tried to determine our position on the map. I found where we crossed the frontline, decided where to look for the target, and just turned to the right to see the possible escape route. Right at that moment, among sparse trees, we saw a group 12-15 Germans in only 30-40 meters from us. The Germans quickly stopped, turned toward us and began taking the submachine guns off their shoulders. I froze for a second, and then thought of an idea - showing no surprise, no alarm, I looked at them calmly and continued pointing toward the escape route. My scouts caught on and continued as though nothing happened. It saved us. The adversary silently turned to the left and walked off toward the frontline. In the first following moments, I could not even comprehend what just happened, as though in a dream. I think that the Germans, seeing our coolness, thought we were Germans, too. They could not think there would be Russians so far into their territory. Later, it turned out this was a group going to rotate those who were in the trenches the previous night. We found ourselves sitting by their usual pathway. What worked to our advantage was that we were dressed in camo similar to theirs and everybody was without a hat.

Many years have passed but I will always remember this.

As soon as the Germans left, we moved closer to the construction area. We were much more careful and moved slowly, studying every inch of the ground. Finally, the darkness fell. It took us an hour-and-a-half to two hours to close in on their positions and find a dugout. The assault had to be silent so that we could safely leave and cross the frontline again where we came. I assigned three strongest scouts to the attack, privates Rybin, Roitman and another one, I do not remember his name. The others remained close by to be able to support the assault with fire if necessary. The brave three began crawling toward the dugout. The tension was enormous, something could happen any second, everybody was fully alert. And then the silence of the night was torn apart by two shots. Our tension went to the limits and then we heard rattle, screams and intense gunfire. The very minute I was ready to run toward the fight, the scouts showed up with a captive. When they entered the dugout, they stumbled upon two sleeping Germans, who immediately woke up and started screaming. The scouts tried to drag both of them out, but the Germans fiercely fought back. They shot one of the Nazis and took the other prisoner. At the same time, the Germans who were in the nearby dugouts, hearing the screaming and shots, rose alarm and began firing around. The whole fray took only a few seconds. Now, our team, without a loss, was all back and we began retreating while there still was confusion in the enemy's camp. It was a difficult march as we were running straight toward the frontline, stumbling upon rocks. As we approached the frontline, it was already dawn. We didn't notice any pursuit, but when we crossed the river and ascended the opposite bank of the Sredni Verman river, the adversary artillery fired several volleys at us.

The visibility was good and they apparently were watching us. We were crossing a clearing in the forest with scattered boulders. Using the rocks as cover, we hurried toward the treeline to avoid losses. Some of us, however, already were wounded and our captive was killed by a round's fragment. Under the circumstances, we ran as fast as we could, carrying our wounded under artillery fire. On return, I reported to the staff commander about the mission. From the captive's documents, we learned his unit number and the location of their battalion's headquarters, for, incidentally, that was what we attacked. Despite the exceptional action of the group during the mission, nobody was put forward for decoration. The staff commander told me that, if we had brought the captive alive, we would have gotten the same kind of order as on his chest. He had Order of the Red Banner.

Episode 3.

In January 1942, having returned to my regiment from the hospital, I was assigned commander of the regiment's intelligence unit (foot and mounted reconnaissance). Soon I received a new mission objective - infiltrate the area 5 km northwest of Lake Tolvand and get a "talkie". This area was on the adversary's right flank, behind the lake, where their units held fortified strongholds surrounded by minefields. I would like to mention that only a month later I stumbled on a mine in the same area and was badly wounded…

After quick preparations, very early in the morning, I checked every single one of the thirty handpicked scouts and asked if anyone was sick or just reluctant. Everybody was feeling well and eager to go. We were going on foot even though the snow was deep and fluffy.

The moment we were setting off, the night was frosty and quiet, the sky clear and starry. The moon was up and shining bright. Somewhere on the frontline, were sounds of gunfire, short automatic bursts, somebody was shooting flares. We crossed our battalion's defenseline and disappeared behind a low hill. It was difficult to walk - the snow was too soft, the scouts grew tired fast, especially the ones leading the group.

Some time later, we approached Lake Tolvand - where it was about 2.5 kilometers wide. Walking along the lake shore for 40-50 minutes, we reached the bank and briefly rested. Then, we circled an inlet and, after a while, saw a little house. This place was in a kilometer-and-a-half from the enemy strongholds. We didn't want to walk into a minefield and I decided to wait until dawn. It was pretty frosty and I thought we could use the house for rest lest the men get frostbite. Outside, we left two guards who were to be rotated. It was quiet and peaceful in the house and some were already dozing off when we heard a real gunfire. It turned out, one of the scouts gathered litter, wood splinters, and paper, stuffed everything into the wood stove and lit it, but there were rifle rounds in the litter.

The sun was rising and we had to leave at once, fearing that the adversary could hear the gunfire. In a single file, we moved toward the strongholds. As we reached a clearing in the forest, we were able to see forward up to a kilometer-and-a-half. We continued pushing ahead, rotating the ones working the trail.

After 600-700 meters, we saw a group of Germans moving toward us. They were on skis, their single file stretched over some distance and they were very conspicuous on the white of the snow. Our scouts, in their new white camos, were almost invisible on the white background. I made the decision to ambush the Germans and split the group in two: the one, under command of the political officer, Lt. Litvak, took the left side of the clearing, the other, under my command, went on the right side, at an angle. The German group was very visible in the clearing. Everyone was told to open fire on my signal - a handgun shot. In 6-7 minutes, the adversary numbering 20-25 men, skied into our ambush. I remember their leader, an unshaven, sweaty redhead with a submachine gun on his shoulder. Having carefully taken aim, I shot at him at a range of 15-20 meters. Immediately, the entire ambush squalled with automatic fire. It was so swift that the enemy was totally overwhelmed and had no idea what to do. Many just fell into the snow, struggling with their skis, some darted off toward the forest for cover.

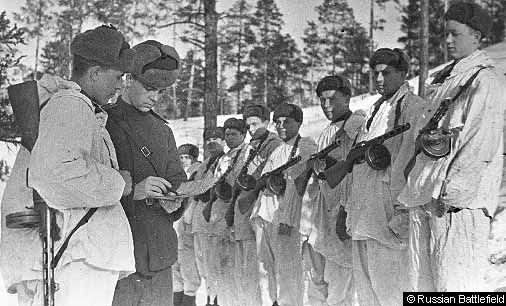

|

A "tongue" is brought in. Karelian front. (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

I was concerned that the scouts would simply kill off all of the Germans; I commanded to cease fire and we rushed into hand-to-hand combat. Sgt. Semenov jumped on a Nazi who was trying to shoot, wrought the submachine gun out and knocked the German off with the weapon's butt. Then, he dropped another one on the run. Lt. Litvak and two scouts already got a "talkie." Private Sukhorukov was tackling a Finn, when Private Murtasaliev came to his help. The Finn was subdued and taken aside. Privates Zvenigora and Klepikov also caught a German who was trying to hide in the snow. Everything happened within seconds. Seeing that the mission objective was complete, I commanded to retreat.

In that short skirmish, the enemy lost eight men dead, including two officers, a German and a Finn. Three soldiers were taken prisoner - a German, Finn and Austrian. We collected the documents off the dead, took their weapons and skis. The recon group did not lose a single man. We were lucky to have large fluffy snowflakes begin coming down when we were returning back past the lake, it hid us from the enemy. Happy and satisfied, we approached the battalion's outposts, where the deputy staff commander, Cap. Vasiliev, was already waiting for us. "How did it go?" - he asked. "A complete failure," - I answered. But he said he had heard the fight and already saw the scouts' faces, he already figured everything went well. We then had some breakfast, fed the prisoners and headed for the regiment staff. Later, there were articles in the army papers about the 596 Regement's recon group successful actions.

Episode 4

During the war on the Karelian Isthmus, army scouts carried out various duties, depending on the circumstances. Not only they acquired information about the enemy and terrain, they were sent to search for command centers that went incommunicado, they served as couriers delivering orders and commands, they searched for unit documents and archives lost in combat; they even delivered propaganda flyers and posters on the enemy's territory - this was done especially often in the defensive. I would like to tell you about one example when the scouts were sent on a mission of finding an important mapcase which had been lost in combat.

In late August 1941, units of the 122nd Rifle Division were fighting and retreating to a transitory defense line at Alakurtti. At the end of that day, our battalion was approaching the assigned position where we were to render cover and support for the retreat of the division command center and its artillery. Because of heavy losses in prior fights, the battalion was weakened.

The battalion's companies were crossing a rugged terrain. The wooded hills changed with marshy areas and thin forests. The reconnaissance platoon was working ahead of the battalion, within the visibility range. It was already dusk, but we still could see quite well. Walking along with the platoon, I suddenly saw a German unit marching on us from the right, in 200-250 meters, apparently, trying to intercept us. I made gestures back to the head of our file but they did not react, nobody was watching us. I was really worried and, realizing we did not have any time, decided to open fire at the enemy to draw the attention of the battalion commander. Hearing the gunfire, the battalion instantaneously went into battle formation and opened heavy rifle and submachine-gun fire supported by mortars. The exchange was intensive and lasted for about 30 minutes. It was already dark and raining. The battalion took the opportunity to break out and take defense at the assigned time.

|

Having gone for about a kilometer, the commander decided to make a stop and check on men in the units. During the fight, several soldiers were wounded. My platoon and I were with the battalion commander. During the break it was discovered that the regiment's party secretary, who was with the battalion, lost in the fray his mapcase with all the paperwork in it. The battalion commander immediately turned to me and said: "I know the scouts are all exhausted but we need to do everything to try and find the lost mapcase." One can only imagine in what condition the scouts were. They did not have any rest for two days, were always in action, carrying out various missions in prior fights. And now, wet to the bone and worn out, they had to get back to the battlefield and find a mapcase. The rain strengthened, we were shivering - it does get pretty cool at this time of year north of the Arctic Circle. Trying to concentrate, I was recalling the fight, especially the terrain and layout - where were our units, where was the enemy. I was taking into account the possibility that the enemy could still be there or somewhere nearby, this made our mission really dangerous. Moreover, in the dark, we could simply run into them. Thus, we disembarked on the mission. We followed the same tracks and trails that we just took leaving the fight. We moved slowly, listening carefully, engulfed by pitch dark. First, we searched a 100-300 m wide strip, then we turned around and started again. Going back, we noticed a glowing campfire on the edge of the forest. We got alarmed and acted even more carefully. Having finished the first strip, we started searching the next one. 20-30 meters through, I heard somebody's stifled but excited voice on the right: "Here it is, got it!"

It is impossible to imagine how much thrill and relief we felt that moment. What an enormous load just fell off the shoulders of my exhausted and starved people! We quickly reassembled and silently moved back to the location of the battalion, increasing the pace as we were closing in. We already knew the way and the yearning to get it over with was growing with every step.

In good mood, we safely returned to the battalion. I immediately reported to the commander about the mission completed successfully and without loss. I handed him the find and received his appreciation. Shortly, we were moving again to a new defense line as had been set forth by the battalion's objectives.

I.L. Kobets, then Lieutenant, Commander of Regiment Reconnaissance, now Colonel in Reserve.

| Translated by: | Alexei Gostevskikh |

Interview

- In 1939, barely three months after I graduated from the teachers college and began working as a schoolteacher, I was drafted and sent to the Pukhovichi Infantry School located near Minsk. There were three battalions at the school - one put together with cadets of the Leningrad Red Banner Kirov's Military School - they had already underwent a seven-month training there, the second battalion consisted of sergeants, who had been in the army for twelve to eighteen months, and the third battalion - us, civilians. The training was really hard. We studied every day, twelve hours without breaks, and finished the three-year program in a year-and-a-half! We were taught mostly the infantry tactics: offense, defense, how to deploy, fire, and dig the trenches. We also studied the weaponry - artillery, mortars, tanks. It was tough ... Everything was done on foot! You are carrying the rifle, plus a Degtyarev machine-gun or magazines for it - at the school, only battalion commanders were entitled to have a horse.

In May 1941, the school was relocated from the vicinity of Minsk to Veliky Ustyug, where we were supposed to graduate on the 19th of June. Everybody wanted to get a vacation leave after the graduation but the commanders told us we would get it once we got to our assigned regiments.

Ivan Kobec, 1941 |

So, I was given the rank of Lieutenant and assigned to a base in Zapolarye (Arctic Russia). On the train, only a half-an-hour to Leningrad, we were told that the USSR was in a state of war. The train halted. A captain got us together and said - "This war is going to be serious. It's fighting 'til the end." That was how he put it, not the way we were taught - "with lesser blood, on the enemy's territory." Thus, we arrived to Kandalaksha and were immediately taken to positions at the border, to the 596th Rifle Regiment. I was issued a gas-mask, a gun and a helmet. This was how the war began for me.

The Germans attempted to breach through our sector but we fought off - our division had been deployed untoward the border just a day before their attacks. They launched a major offensive on July 1st and our 122nd Division held the German 36th AK for seven days. Later, we pulled back to the Kairala defense line, already held by the 104th Division. I must mention that back then we didn't have scout or reconnaissance units in battalions - only on the regimental level. The constantly changing conditions demanded constant information feed and the battalion commander ordered me to put together a 'hunters' platoon. I did, and commanded it until the winter of 1942.

Reconnaissance is a very hard work. And we didn't have any special training! We had this peculiar episode in the first days of the war. The Germans were trying to skirt our positions on the right. The battalion commander sent us to take a watch on the road and observe their movements. We went as close to the road as possible and lay in a marsh for 24 hours. Bugs, mosquitoes! It wasn't possible to breathe, let alone observe! We were covered in our own blood. On the way back, I noticed that the Germans were building a bypass from the road to Kualoyarve, directly into the right flank of our battalion's position, obviously for a straight run to the nearest commanding height. When my group was crossing their defense line, we had to go across a clearing in the woods; I sensed that we had been detected and they would try to intercept us. Indeed! And then there's this moose rushing at us! Yes! Somebody must have scared him off good. I tell my people to halt and take cover. Just as we settled down, we noticed a group of Germans descending from the slope. For some reason, I best remembered the insignias on their caps. We let them come closer, showered with grenades and finished off with rifles to clear the way. As soon as we got to our positions, I reported to the commander of their plans to take over the heights. Unfortunately, nobody took heed of our information. The Germans took the heights, dug in and our defense became impossible - they were seeing all of our regiment's positions and all the way inside. The commander realized this - the situation was bad, the Germans must be knocked off. Easy to say - our losses were mounting. Had anybody listened to us, a single company could have held the heights forever.

|

Let's smoke! Infantry resting (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

- How often did you do reconnaissance missions?

In the first months, July to November, we went out every two-three days. Later, when the frontlines got established, it became very difficult - barbed wire, minefields, snipers' landmarks set at the ready. All this required very serious preparation - studying the target, terrain, approaches. And still, to fetch a "tongue" at the edge of the defense line was very, very difficult. It was easier in the rear or on the flanks, where they had sentry stations or patrols and we could set an ambush on the trail or ski track. At that time, we went on missions once or twice a month.

65 SMRB, 1942. (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

- Did you dress to be indistinguishable from your men?

In the summer of 1941 I did blunder. We were on a reconnaissance mission. The deputy platoon commander and I - in officers' greatcoats, and, as though this wasn't enough, with shiny, star-adorned belt buckles on top. There were 12 men in the group. So, we make it through their outposts. But we yet have to pick a target! The men lie down, I tell my deputy - "Let's move a bit forward." So, we crawl forward, he and I. I rose on one knee to point to something for him and - it was only "Zi-i-ip!" - and I'm on the ground. I got lucky - the bullet entered my leg below the knee, between the bones. The German sniper was in the trench only 15-20 metres away and was aiming my legs on purpose - to wound and capture. He did see I was an officer. He kept my men down, and I couldn't move on my own anymore. Finally, they threw me a rope and just pulled me out. If it wasn't the officer's greatcoat, he may have simply killed me. Yes, that's what happened. Afterward, we dressed all the same and one could not tell a commander from a private. It must be said that back there we were pretty well outfitted - warm underwear, wadded pants, furcoats. Though we had problems with boots sometimes - on that rocky ground, they wore out fast. As far as camouflaged outfits are concerned - we didn't have them. Neither did the Germans, by the way.

- How well were you fed?

It was mostly porridge. We had a variety of canned food: at first, Russian, mostly fish, and later - the lend-lease stuff - canned meats. At lunch, we would be given a soup, porridge with canned fish or meat, and tea or dried-fruit drink. In missions, we took along rations - biscuits (croutons), canned stuff, sausage, sugar, butter. We didn't have any chocolate though. We were also issued pure alcohol, but only to combative units, 100 grammes per person each day. We also had spirit lamps - fueled by a mixture of alcohol and stearin; people simply extracted the alcohol from that fuel. I never took alcohol on a mission. First, it was issued daily, at night, and we wouldn't have been able to get enough for a mission. Second, if you do take enough - it all would be consumed at once, and a drunk soldier is just as good as a wounded or dead soldier, without a question. That's how a friend of mine, Nikolai Aleksandrovich Makarov, was killed. He was on an observation post, waiting for his group to return. So he drank a bit, got mighty fearless - when the group was already coming back with a captive, he just walked out to meet them. In the winter, without the white coveralls! The Germans got him, of course. Hadn't he drank, he may have been alive now. Never did we drink before combat! Afterwards - yes! After a successful mission, the regiment commander himself would issue alcohol, get some extra rations and even sit at the table with us.

- How did you perceive the Germans?

There was a very clear understanding - if you miss him, he kills you. But there was no hatred. If you're at war, that's what you do - shoot and kill.

- Did you have any fear?

The person who has never been in battle - his entire nervous system is under stress. He's frightened by every gunshot, every blast. There are no such people who just come prepared for war, no. But this fright can be overcome. Over time, when you get used to it, you'd understand - this shell is just gonna go by and this one is dangerous. Even after a short time off, say, after being in the hospital, this fright temporarily comes back.

Then again, if you are frightened, you can't go on a mission! Did you know that men sense their leader just as a horse senses the rider? If the horse feels the rider's fear, it won't come near the obstacle! Same here, if the commander is brave, the soldier feels it: "Uhuh! You won't be done for with this one! This leader won't fail you!" The commander's courage and calm play the most important role! I, for example, while in action always thought this way: "If I don't get killed today, I will tomorrow. So what's is there to fear, anyway?" Maybe because of this attitude people always wanted to get into my platoon. I selected them this way: the most important thing - it's the will. Where there's the will, the rest shall come! Because the cowardly, the sick or the weak wouldn't wanna do that! Their physique also mattered, of course. That guy, Volkov (see Episode I), I really felt sorry for him. He was taller than average, big guy, good lad. He says: "I'm hit." I tell him: "Freeze, stay down. Half-a-minute, a minute and it'll be over!" It's easy if one isn't wounded, you press into the ground hard; the wounded - they're frantic. I turn back to him in a second - and he's dead.

So, I could pick out people from the entire regiment. I had a regular staff of 20-25, of course, but when I was going on a mission, I could pick any extra people as necessary. There were always many volunteers among the convicts, because there were more opportunities to earn extra points in a mission, and once the convict got distinguished in action, the commander immediately applied for complete acquittal. I probably had five men like that and two of them had 10-year sentences. They were very good men.

- Did the commanders use you as infantry or saved you for the missions?

You know how every commander took care of his reconnaissance teams? Uhuh! For him, reconnaissance was everything! If the commander is good, he would protect his recon platoon better than his own eye!

- Did you have any privileges, leeway?

No. I only knew that I had to carry out the mission. If you turned back - you are a coward. But it also happened like this: they would take off, get shot at, come back and report - "We got detected." In one of my cases, we got under machine-gunfire, stumbled upon Germans, and still completed the mission. We only didn't save the captured (See Episode II). Though nobody was put forward for a decoration after that.

I never went after promotions or decorations. Once I got called to the division's staff. I was a Senior Lieutenant back then. I arrive and report, and a staff officer asks:

- Why is your uniform out of order?

- How so?

- You are a Captain! - he then took two bars off of his collar tabs and put them on mine.

I was 21 years old when I became Captain. I wasn't lucky with decorations, either. In the hottest days of the beginning of the war - only very few were recommended for decorations. Besides, in our parts, in the Arctic, we got decorated only for actual missions or actions, not like in the West - by assignment. So I have only the Order of the Red Star for that successful ambush (See Episode III).

- What did you think of the Party?

I came to the war as a Komsomol member (Young Communist). Later, after the incident with the documents, when we found the briefcase (See Episode IV), I was noticed in the Regiment and they decided to admit me to the Party. I remember I was walking with my recon men when the regiment's party secretary saw me and told me about the decision.

- What do I need to do? - I asked.

- Nothing. Just write up an application. That's all.

They made me a candidate and after, in 6 months, I was made a Party member. So, I did everything that was asked of me.

- Was there any interference in your reconnaissance activities from the Party functionaries?

No! I had this deputy commander, political officer, Lieutenant Litvak; he never interfered with operations - only looked after the men, so that they are outfitted, fed and aware of what's going on in the country. He really helped me. He would talk to the people, things of that nature. There were nasty political officers, of course, who tried to take charge, but not in my case.

- Did you believe in signs, omens, premonitions?

I had these two episodes. The first one happened when we pulled back to Alakurtti and took defense. The signalman and I were sitting in the same trench when this bombardment started. All of a sudden, I had this feeling as though somebody forcefully pulls me to the side. I only leapt 15 metres off when a shell exploded on the spot where I just was and killed my signalman. The second incident took place when we were moving to the Verman river, in August. We just stopped for a break on a butte, and the Germans were shooting here and there. And then, some force just lifted me in the air and I ran down the slope, 10-15 metres. That very same second, a whole salvo - 6-8 shells, came down on our resting place. There were wounded and maybe even killed, and I was saved only by that leap. The both incidents occurred within seconds, faster than it took to tell about them. But when I got blown up on a landmine, I didn't have any premonitions. We were on a raid behind the enemy's lines. I just swapped places with the two scouts who were leading the way, they were so exhausted they were sleep-walking, and set off a booby-trap. The only thing I can remember is black-red flames in front of me. The guys told me I was tossed ten metres away. What's interesting, had it been only five metres, the fragments would have cut me right down the middle - that would have been the end, as it was - I got them in my legs and in a hand, the one I had lowered. They pulled me out but I never returned to reconnaissance after these wounds. In 1943, I went on a raid with my battalion and had to pull back - my wounded leg got swollen so bad it had to be operated. Later, I served in the 19th Army Staff, in the army intelligence and reconnaissance, with Daniil F. Zlatkin.

- Did you limit yourselves to the standard issue rations?

Of course not - we picked, cooked and preserved berries and mushrooms. Sometimes hunted. In early July 1941, on the division's left flank, there was a trail we always kept guarded. Once, I sent two of my men to get up on the closest hill and watch the Germans. As soon as they went down the wooded gully, I heard gunfire erupt there. I was already thinking about getting down there with my men when these guys showed up. It turned out, they got us a deer. So we were with fresh meat for three-four days.

- What kind of weapons did you use in the missions?

I took a PPSh and a TT. Sometimes we used German submachine-guns. Everybody wanted to get one because they were so lightweight. We also took along F-1 or RGD-33 hand-grenades. German grenades were also handy - they had a longer handle and could be slung farther. If we worked on the edge of their defense lines, we carried along a machine-gun, but never took it for deep raids - too heavy. Sometimes we had artillery or mortar support.

- Were you taught any hand-to-hand combat techniques?

At the military school, they taught us to use the rifle. We had this straw-stuffed dummy and then one of the cadets would stand nearby, armed with a pole whose end was wrapped in cloth - lest the attacker be hurt. And as soon as you get to attack the dummy, the cadet would hit you. So, you had to fence off the pole and poke the dummy. They didn't teach us any special strikes or knife techniques although a knife and knowing how to use it are a must for a scout.

- Did you use different tactics against the Finns and the Germans?

No! The tactics didn't change and we didn't adapt them to the adversary's nationality.

- How many men were usually in the group?

Karelia has such a terrain that even a battalion has difficulties maneuvering, especially in the summer. In the wintertime, we sometimes launched two-battalion-strong raids to make a good hit behind the enemy lines, but most often we operated in small teams that were better suited for those conditions. Usually, only 10-15 men, but well prepared and armed. The Germans typically used larger units - 50-60 troops, supported by artillery and mortars. It was a primitive and ineffective tactic. The Finns, by the way, also operated in small groups. In addition to the terrain, what's also important in Karelia - it's weather. It can change any minute! There was this incident in the 122nd Division. A ski battalion went out on a raid. The weather was good. Then, sleet started to come down and they all got wet. The leader gets through to the division commander and reports that further advance is impossible - they can't ski on the sleet. The division commander responds: - "Carry on with the objective." Disobeying the order, at his own risk, the leader turned the battalion back. At night, the frost bit hard. It was really fortunate they turned back - otherwise, they all would have frozen, although 70 troops were hospitalized anyway and the others were frostbitten.

|

104 RD. March, 15 1943 (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

- How did you assign tasks in a mission?

It depended on the mission. If it was just a target recon, there were no specific task assignments. If the objective was to get a "tongue," I would select 2-3 strongest men for the capture team, the rest would be in the support team which would cut off the pursuit with gunfire and help the capture team get away. It was later when our theoreticians decided there should be three teams: assault, capture and support. What it meant was that one person in the assault team would be specifically assigned to snatch a captive - the others were to make sure it happened.

- Did you train?

Yes! Once the frontline stabilized, before going on a mission, we would select a target - a machine-gun station, a trail ambush and so on. Then we'd prepare. We would find a similar spot on our side, set it up and the scouts rehearsed. What's most important in reconnaissance? It's knowing your target, especially when the objective is to acquire a "tongue." You need to study the terrain, prepare thoroughly, and only then go on the mission. Although at first, it was like this - "Okay, tonight you should get to this sector and get us a 'tongue'." Can you imagine that? All I could do is get my people, decide how to get there and what weapons to take along. Though later we got it all worked out.

- Did you pull out your dead?

We did if it wasn't too far. If we couldn't (as in that case when we were looking for the colonel), we'd just take out some rocks, make a hole in the ground, maybe sixty-centimetres-deep, cover them with greatcoats and put rocks on top. We always pulled out our wounded.

- Did the Germans have many snipers?

We had more. I was also sniping a little. Once, I went to the frontline and saw combat engineers setting up a minefield - the mines were wooden boxes with a TNT stick inside. They would then fill the box with TNT powder, insert the primer in the stick and set the mine up. So, I lay down with my rifle and kept shooting every once in a while - the Germans seemed to be building some fortifications out there and I could see somebody carry a log or something like that. I'd fire, he'd be gone. Now, those combat engineers, there were three of them, and they had two sacks - one with the sticks and the other with the powder. They would assemble several mines and then carry them over to set up, maybe three at a time. The primer must be inserted the last minute, already on the spot, but they didn't want to do it lying in the marsh. I said: "What are you doing?! You want it to go off in your hands?!" - "Nah, - they said. - Look how many we've done already!" Only forty minutes later I heard two powerful blasts.... Only one leg was left of those three....

| Interview: | Artem Drabkin |

| Translated by: | Alexei Gostevskikh |