I was born in 1922. When the war started I was a workman at a machinery plant in the town of Khimki, near Moscow's vicinity. As many coworkers I had the bronia - the status of being exempted from military service with no medical grounds.

In the fall an announcement was declared: all male Khimki's residents of call-up age must present themselves at the voenkomat - the military registration and enlistment office. Well, the next day, along with several my neighboring friends, I visited the voenkomat. They required me to present my passport but I couldn't. The point was that because of my bronia, the plant's personnel department had taken away my passport and gave me a special certificate with a red star on it instead. As soon as the military commissar read the document he refused to draft me.

I left the office and told my friends that were waiting for me: "That's all. They couldn't take me." My friend Liosha Orekhov said indignantly: "What the hell! In an hour put my coat on, change your hat, too, and enter again. Tell him that your plant had been evacuated recently and that you want to fight at the front." And I did everything that Liosha said.

So all of us were drafted and dispatched to the Gor'kovskaia Oblast' (province) in a village of Panfilovo, not far from the city of Murom. There was a training unit there, and I became a machine gunner. I learned to fire both the "Maxim" and the "Degtiarev." Also I mastered the German MG - a good machine gun: elementary bolt and not many components. Moreover it is lighter than a "Degtiarev."

In January 1942 we were uniformed and on about the 20th they dispatched us to Moscow. I served with the 367th Separate Artillery-Machinegun Battalion of the 152nd UR (Russian abbreviation of the fortified zone).

At first we were armed with German rifles and machine guns. My machine gun was manufactured by the Czech machinery company Skoda. All of its main parts were made of special steel and never rusted. Later they gave me the "Degtiarev" - its metallic components were burred all over. Moreover, as soon as the machine gun became a bit wet, it rusted and you must clean it.

We were placed in the MZO (Moscow Zone of Defense) between the towns Gzhatsk and Mozhaysk, near the museum of Borodino. The zone had been fortified already: there were there concrete hoods ("mini-fortresses"), defensive structure formed of earth and logs and other field-engineering defensive installations, particularly the minefield. The road was mined as well. All of would-be targets were zeroed in on. (I was able to fire through an embrasure even at night).

Our battalion was in the second echelon. We only learned our armament and equipment but at the same time the battalion was on round-the-clock duty. The Germans didn't harass us but the command inspected us regularly.

The main thing was that we suffered from hunger terribly. 600 grams of bread (in winter it was frozen) and a scoop of water with several minor pieces of pasta in it - that was our daily ration! We talked only about food. We shot rooks and crows. We ate horses. We barely walked and didn't even wash our faces. In the spring 1942 we planted potatoes and cabbages. All of that was our life until September 1943.

Initially the battalion went afoot, then trucks delivered us to a forest. We didn't sleep for three days running. At 1:00 a. m. our commanders finally came.

- We will attack the Svishchevo village right now.

- Where? Why?

- It is over here. There is nothing in it!

Well, we started off - peace and quiet. However, the Germans aren't foolish - they cut down all the alders before the village and zeroed in on everything. They let us in and then suddenly opened fire! Our whole company was killed, only four of us came back. My machine gun remained there. Later the Germans left the village by themselves.

Soon we continued the offensive. One day we marched 60 kilometers and liberated a village. The Germans had occupied it for almost three years. As soon as the inhabitants saw that the Red Army troops arrive, they became so happy! They kissed us so passionately!

- Just now the last German left the village. He motorcycled along it setting many houses on fire. You were a bit late. You are hungry, aren't you?

They tried to bring some food but we were in a hurry - we should go forward:

I really can't forget that meeting but I also can't forget many sad, even terrible events. Here are some of them.

Once, being in the second echelon, we were laying in a potato field by the Dnieper River's bank. On the opposite bank another detachment took its position. At 8 a. m. Red Army soldiers began their attack: "For the Motherland! For Stalin! Hurrah!" Many of them were mowed down on the spot by the German machine guns. The detachment lay down and everything became silent. In some two hours we heard again: "For the Motherland! For Stalin!" but that attempt failed again. There were two more unsuccessful efforts to attack the enemy. I thought to myself: "What is that for? They definitely see that there are a couple of machine guns. Why then not to organize an artillery or air bombardment before the attack? They didn't do things that way - an entire field is covered with corpses:" I can't be a judge but it seems to me that they didn't spare people at all:

Of course, we, the soldiers, didn't think that we could be killed. We just fought - it was our job. You were thinking about firing and didn't feel fear. It was quite another matter when you found yourself under artillery bombardment - yes, you feared for your life:

Another sad episode. Once we were placed on the edge of a forest and began digging emplacements and foxholes. Three comrades asked me: "Misha, go to the field-kitchen, we are hungry." I gather the mess-kits and went. At that very time the German bombers performed a raid at our position. As I returned there was none to be fed - all were killed:

Now I'll tell you a very sad story of what took place when all our rear services hopelessly remained far behind the troops. The reasons for this situation were the blown- up bridges and soaked dirty roads. There was no arrival of food for five days running. At last an order came: select a dozen of strongest soldiers and dispatch the group to the Rear Service Department, some 30 kilometers apart, for dried bread. I was a member of that group.

We passed a partly burned village, many villagers dwelled in dugouts. I entered one house - there was a family of six there. I asked a young woman for a tiny piece of bread. She refused: "Where can I find it for you? Do you see our four children?" In a moment I heard a voice of an old lady who was lying on a Russian oven: "Daughter, give him what he is asking for. Maybe your husband is also begging somewhere as this soldier did?" I received a piece of something that hardly resembled bread. Nevertheless, as soon as I took it - I swallowed it in a moment:

After we arrived to the rear services department I heard how the department's doctor said to the local sergeant-major: "Cook a hot cereal for them and don't permit them to eat the dried bread. Otherwise they would overeat and may die." We ate plenty of hot cereal in that evening and in the next morning. Then they gave us twelve heavy rucksacks with dried bread for our entire department, and we set off. Despite the recent warning, none of us was able to restrain himself and we began eating the dried bread. As a result, two or three soldiers of twelve died of twisted bowels when we were on our way back:

Well, our offensive operation continued and on 25 September we were liberating the city of Smolensk. Then after several fights we entered Byelorussia and on 22 October 1943, we were already in 18 kilometers from the city of Orsha located by the Dnieper River. Our battalion seized a height with a German trench on it. Our commanders informed us that the Germans are going to attach the height in the next morning. Therefore, food for a breakfast and dinner was delivered tonight.

The Germans started their artillery bombardment when the day was just dawning. Oh my God! Everything became mixed with earth. In half an hour their tanks moved and several groups of infantrymen followed them. Both my friend Kolia Friger and I began firing at the infantry (I fired the "Degtiarev" and Kolia fired the "Maxim"). We killed many of infantrymen and the tanks stopped moving in about 200 meters from our trenches. By that time my machine gun's round magazine was empty, so I raised myself to replace the magazine. Most likely, the tank crew caught sight of me. I only saw the flash of a shot and at the same moment a shell exploded at the parapet. I was seriously wounded in my back and wounded in the ear. I couldn't walk by myself, and Kolia helped me to reach the Dnieper's bank. Here a male nurse bandaged my wound and I was delivered to our medical company.

The Germans started their artillery bombardment when the day was just dawning. Oh my God! Everything became mixed with earth. In half an hour their tanks moved and several groups of infantrymen followed them. Both my friend Kolia Friger and I began firing at the infantry (I fired the "Degtiarev" and Kolia fired the "Maxim"). We killed many of infantrymen and the tanks stopped moving in about 200 meters from our trenches. By that time my machine gun's round magazine was empty, so I raised myself to replace the magazine. Most likely, the tank crew caught sight of me. I only saw the flash of a shot and at the same moment a shell exploded at the parapet. I was seriously wounded in my back and wounded in the ear. I couldn't walk by myself, and Kolia helped me to reach the Dnieper's bank. Here a male nurse bandaged my wound and I was delivered to our medical company.

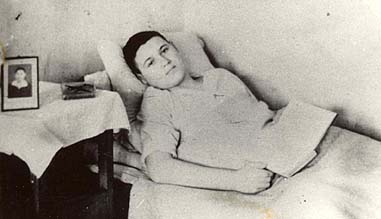

Since then I had been transferred several times from one hospital to another. When I was in the first hospital my friend, who helped me to reach the Dnieper, visited me. He told me that the Germans attacked our position on the height four times but we withstood.

My treatment odyssey finished in Kuchino hospital where I was for nine month and underwent four surgeries - they removed the fragment from my back. Actually that was the end of the war for me.

| Interviewed, recorded and initially edited the Russian text by: | A. Drabkin |

| Finally edited the Russian text and translated it into English by: | I. Kobylyanskiy |

| Edited the English text by: | T. Marvin |