The great battle has begun

Ever since the spring of 1941 people had been feeling the breath of a large approaching war.

At the time, I was working in the Leningrad's Research Institute as a senior engineer. While there we were taught about anti-aircraft defense. After work, in the Institute yard, we dug slit trenches and we would also wear gas masks and pretend to work for half an hour. This is how we prepared for a real gas attack.

The night of June 22nd was a warm and bright evening. It was graduation time for many schools, and I was coming back home after a party. I had met many young people there. Girls were wearing their long white evening dresses and high heel pumps. Their thin heels merrily tapped on the asphalt roads. Peace and quiet were all around. Somebody had crooned the popular foxtrot melody 'In some place in Tahiti. …' But we were far from Tahiti and terrible events were coming. We did not know that the bloodiest war in human history was to begin in a few hours.

The next morning I went out to buy food. A huge crowd surrounded a loudspeaker which was mounted on a post. I heard the stammering voice of foreign minister Molotov, "German aircraft have bombed our cities without a declaration of war. There is a fierce battle at the border. Our brave border guards are beating off an invasion by frenzied (ogoltelyi - no direct translation into English. This word means out-of-control anger but in a directed fashion. It was often used in propaganda announcements so has some political connotations - JQ) enemy soldiers." I do not remember his words exactly, but that is how they are in my memory.

We felt the approach of war in our everyday lives long before the fighting started, but no one expected the war would begin as soon as it did or last as long as it did. Nor did we expect our defeats would continue for a long time. Everybody knew our wise leader's words, "We do not need alien land, but we will not yield an inch of our own land." We sang, "We will destroy our enemy's army on their own land with one strong blow. There will be little bloodshed," but the reality was different. By September the Germans were close to Moscow and Leningrad.

In the middle of June I received a notice to appear at a military commissariat (draft office JQ) at the beginning of July. I did not want to wait until this date so I went on the morning of June 23rd and got in line. The atmosphere was noisy and chaotic, many men were cursing. Captains, majors and lieutenants were rushing from room to room with papers. An orderly officer read my notice and yelled at me, "Are you illiterate? It is clearly written when you have to be here! Do not disturb me, go home!" I answered, "But the war has begun. I know German well, I can serve as an interpreter!" The orderly officer did not listen to me, "Don't give me any crap! Get lost!"

My father had been mobilized the first week of the war. My mother and I went to see him off at the Warsaw Station (one of the major train stations in Leningrad. JQ). Brass bands were playing, youngsters were singing "Come back soon with victory." Many of these men, including my father, did not come back at all. For him it was a trip to nothingness.

The last letter we received from him was dated September 8th 1941. He wrote, "I've had many remarkable achievements. I've learned to play dominoes and been masterful performing surgery." We never received another letter. We spent a long time not knowing what had happened. Every time we inquired we got the same answer, "He is missing in action." Finally, at the end of December 1941, we received a letter from a woman he had worked with. She wrote that near the city of Staraya Russa their hospital had been bombed and my father had been killed by a bomb fragment. No one but my father was killed. The poor fellow did not have much luck. We could not find out where his grave was or even if a grave existed at all.

Everybody was waiting for a speech from Stalin. On July 3rd he finally spoke on the radio. It was the 12th day since the invasion began and already the enemy occupied a large part of our territory. He started his speech with the words "Brothers and Sisters." He had never spoken to the people in this intimate manner before.

At the beginning of July 1941 the government announced the creation of the Volunteer Army. Everybody could join this organization, even those unfit for regular service or people who had been withheld from the draft due to their special skills (as I had been). The draft officer assigned me to a newly forming People's Reserve Division, which was short-staffed in junior officers and enlisted personnel. There were only enough men for the division to form a single regiment. The leftover officers, including myself, were sent to a reserve center located at a school on Krestovsky Island. We shared the school with nurses nearing the end of their training. During wartime, everything is forgiven, so you could imagine what was going on there.

Every day we waited for messages about our army's counter-offensive, but we had to wait for a long time. At the beginning of August an armored unit's officer showed up at our division. He asked who was familiar with the operation of a tank's radio set. While in military reserve training in 1939 I had studied them and thought I could do what he asked. But my wishes to see some real fighting did not come true. I was again assigned to a reserve unit, only this time to a reserve tank unit. I became the commander of an entire heavy tank regiment's communication platoon stationed at the Polytechnic College.

At the beginning of September the Germans occupied Shlisselburg, cutting the land connection between Leningrad and the rest of the country. There are a lot of books describing the starvation, the cold, the heroic behavior of the besieged city's residents. I am not strong enough to write a new one.

My niece Natasha was evacuated to Tashkent with the conservatory school that she had entered that spring. My mom joined them soon thereafter. Nine of my close relatives stayed in Leningrad during the siege. Only two of them, aunt Sonia and my cousin Victor, survived. The rest died of dystrophy caused by malnutrition.

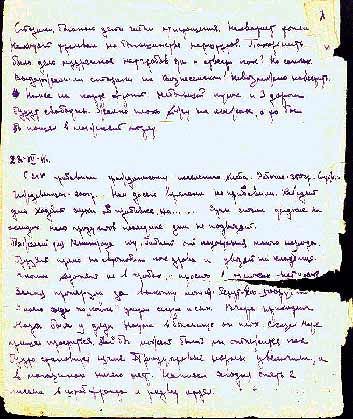

I started keeping a diary during the early days of the war. I carried it all the war in my army backpack. It looks shabby now but I still have it. Below are some fragments from this diary.

|

August 17th, 1941

This is the 56th day of the war, and my 47th as a soldier. But I am assigned to the 12th Reserve Tank division stationed at Leningrad's Polytechnic College campus. I am the commander of the communication platoon with only one broken radio, a 71TK. Military representatives sometimes come and select men who have already seen combat to join front line units. It is sad and hard to listen to broadcasts about our cities falling under enemy occupation. The Germans continue to move quickly further into our country.

September 10th

For the second consecutive day the Germans have heavily bombed Leningrad. The night sky is lit by the glow of fires. The Bodaevsky depots, stocked with basic food supplies for Leningrad's people, are on fire. When the air raid siren sounded at first I could not get the men to go into the slit trenches. Then a bomb exploded so near that the glass in the windows shattered. After that the men ran out to the trenches, pulling their pants on as they went. The Germans have forced the Dnepr River and occupied Kiev. I dreamed about big, tasty Antonovsky apples this night. They were large, juicy and delicious. Why did I have this dream?

October 1st

The Germans have bypassed Pushkin and advanced on Pulkovo. The Pulkovo's observatory is on fire. For several days already they have shelled Leningrad with long-range artillery.

In the morning we watched deserters being executed in the vacant plant near the Polytechnic College. This was done as a lesson for us. We stood in a row to better see the executions. There were three deserters, all tank crew-members from our company. Two of them wore their pilotkas (military cloth caps - JQ) and one wore a tank crew helmet. All three had blank stares on their faces. Probably they had already said goodbye to their lives. They were undressed and stood in the snow in their underwear. It was an early snow this year. As they stood there a grave was being dug close to them. They had run from the front, abandoning their tanks.

They were faced into the firing squad. The soldier in the tank helmet covered his eyes with his arms. They went up to him and forced his arm down. "Shoot the traitors of the motherland," commanded the senior officer. Blood flew from their faces and all of them fell. Two still moved. An NKVD man walked up and shot these two in the head with his pistol.

The enemy is in Ligovo, at the gates of Leningrad. Artillery bombardment has become so commonplace now that nobody rushes to the bomb shelters anymore. When the air raid siren sounds it has again become difficult to get my soldiers to take cover in the trenches. All of the commanding staff have been given a food card to get meals at our cafeteria. The barracks are not heated. Our thin blanket and overcoat cannot save us from the cold. A handyman made a small stove. We use logs from the nearby bombed-out structures for firewood. We run this stove 24 hours a day, but it is so cold that it does not help.

I was given leave to visit my home for twenty-four hours. The Putilovsky plant area was bombed and twenty-two people recently made homeless have been sheltered in our apartment. My older brother Mark and I made soup by boiling dry seaweed. Our mother used to add it to her bathwater to fortify her nervous system. Now we use the seaweed to fill our stomachs and it seems very delicious to us.

The children of Leningrad are being evacuated. There is only one way to get from Leningrad to the mainland, over Ladoga Lake. All railroads and highways to friendly territory are cut off. The South and East are now blocked by the Germans, and to the North by the Finns. Yesterday my mother's brother, uncle Naum, and his family crossed Ladoga Lake on a barge.

German aircraft activity has escalated. The sky glows. The Institute of Applied Chemistry and roller coaster are burning. Our troops have abandoned Odessa.

October 23rd

A TASS news report announces "this is the fifth day of intense battles in the Mojaysky, Maloyaroslavsky and Kalininsky regions." German troops are close to Moscow. General Zhukov has been appointed commander of the entire German front. Another of my letters to father has been returned. I worry, "What has happened to him?" I would like to believe he has been transferred to another division.

When I was in the city I went to a store, just to look around. While I was there a fat woman started a commotion. "Why do you show sweets in your store window? 'Mother, buy me a candy' - my children are crying. You sellers probably guzzle as much food as you can. But you cannot sell candy to a child without a food card!?!" she yells and shows the clerk the kookish (obscene hand gesture indicating disrespect - JQ). An old man with an emaciated face and yellow smoker's fingertips supports her, 'Yes, I cannot buy matches without a food card. We'll break the glass and take them!" But no one dares to do that. If they actually carried out their threats they could be executed.

The food in our dining room has become even worse. We have just 75 grams of bread for each breakfast and supper, sometimes with a small piece of cheese or sprout (small fishes - JQ), and tea without sugar. For dinner we receive a plate of thin soup and 200 grams of bread. Sometimes a bowl of bean soup is added. I have never suspected that bean soup can be so tasty. I am becoming weak, it is getting difficult for me to climb upstairs.

Tough fighting continues near Moscow. I handed in a request asking to be sent to a unit at the frontline to my division commander. He would not accept it and sent me away. Our troops were driven out of Stalino (Donetsk, city in Southern Ukraine - JQ). Fifty thousand Germans were killed there. People say, 'we bit thousands of them, but they still advance.' Everywhere people talk about food.

November 7th

Today is the anniversary of the October Revolution. Yesterday, because of the holiday, we were given a half liter of wine. We drank the wine during one of the air raid alerts. Today there was was a "parade". We marched around the Polytehnic Institute. Soldiers asked for candy, just like children. There has been no news from my father for a long time. I worry how he is.

I was on duty in the kitchen and made friends with the cook. At night our friendship became closer. The next day my brother visited me and she gave him a bowl of soup when I asked her.

Leningrad's Pravda headline today read, "Leningrad is encircled. One cannot expect food improvement until the enemy encirclement is broken."

Yesterday there was a call for volunteers to enlist in a break-through division. Only ten people were selected from my unit. I was not accepted because I still had not seen any combat.

November 14th

There were three air-raid alerts last night. A bomb exploded somewhere close and the house swayed like a drunkard. It was a quiet moonless night. The Germans are firing into the sky flares hung from parachutes. They brightened the nighttime to as light as noon. It seems that the snow is a blue, the trees shadows look like huge spiders extending their tentacles to the trenches we sit in. Anti-aircraft gunners tried to shoot down the flares. Tracer bullets, red, blue and green, striped the sky. It was magical and beautiful like being in the garden of Gassnardon (state-owned palace open to the public - JQ).

At eight o'clock in the morning the air raid siren sounded again. The trenches were cold and wet. Our legs got cold.

The division commissar promised to recommend my transfer to the paratroopers. I am afraid I will not be accepted again. Our daily bread ration was reduced to 300 grams. It is our main food. It is said that the bread is made of 40 percent sawdust.

It is rumored that a mysterious gun is moving from area to area as it fires on Leningrad. Volunteers from our division tried to find it. They thought they had found it in Udelniy Park and then again at Ts.P.K.O.

Evidently the volunteers had hallucinated due to starvation.

November 16th

Heavy bombardments each of the last three nights. My soldiers go to the trenches only with difficulty. We are all becoming fatalistic. It is said, "The one destined to be hanged will not drown, there is no escape from fate, might as well sleep."

An order was issued: "Everyone has to sleep dressed. In case of air-raid alerts everyone is to rush into their slit trenches." Yesterday I was in the city and went to my former place of employment. Grub is all people talk about.

December 6th

My brother sold our piano for pennies. He also sold our dining room furniture, father's fox fur coat and other things that have been part of our life since I was a child. I remember my father wearing his fur coat when he returned from house calls on his patients. Where is he now? What has happened with him? It is better to think about how to help your relatives than to think about what is going on all around.

A black marketeer came over to buy our stuff. He said, 'I am one of your father's old patients so you should charge me low prices, for old time's sake." What kind of logic is that? He tried on father's fur hat in front of a mirror. I said, "This hat is becoming on you" instead of doing what I really wanted to, punch him in the mug and kick him out.

Still no letters from father. I still do not have an answer to my request to be sent to the front and work as an interpreter.

December 10th

It is minus 20 degrees Celsius and windy. The army is somehow still fed, but civilians are dying from starvation. They drop like flies in late autumn. Yesterday, I got permission to visit my home for twenty-four hours. I promised the chief of staff that I would bring back a gramophone from my home.

My brother Mark and I broke up the small table that I and later my niece Natasha used to do our homework on. It was a pretty white table. Mark and I bathed in a tub facing each other. The water was heated by burning the table. It was not bathing, it was nirvana. I'd not washed in a month but, thank God, did not have lice. In the evening my brother, his friend Igor Mukhin and I all sat near the small stove where the rest of the table was burning. We drank chicory coffee without sugar and talked about food and the situation at the front lines.

The Germans have concentrated 31 infantry, 10 tank and 7 motorized divisions at Moscow. TASS reported, "Our troops have launched a counter-offensive and pushed the Germans back 50-100 kilometers from Moscow."

December 12th

Japan has unexpectedly attacked the US navy. The battleship "Prince of Wales" and a cruiser of the "King George" class have been sunk. Japanese forces landed on the Philippines and Malaysia. Everyone believes we will declare war on Japan soon. Our forces have freed the city of Yeltz. Near Moscow 30,000 Germans and 1,500 tanks were wiped out in battles. There is still no news from my father.

December 20th

On December 17th I learned that one of my requests had been accepted and I was accepted into a reserve Communication Company. I was transferred from the signalers to become an armored radio operator and now back to signalers again.

I sent a telegram to my relatives in Tashkent, wishing them a Happy 1942 New Year. What waits for us in the future? Where and when we will meet again? Who will survive who will be lost? Only God knows.

December 21st

This is the third day for me at the new station. I have met many of my schoolmates from the Institute of Electrical Connection mates here and one schoolmate from "Petershul" named Karlin. He told me the intelligence unit of the Front is recruiting signalers who know German. Immediately I sent two reports to personnel and to the Front intelligence unit.

It is said there is little food in Leningrad's stores. A lot of people are dying from starvation. They are being burned in common graves, some in bags some not. There is no wood for coffins. A lot of people have died right on the street. The burial patrol picks them up in the morning and takes them to a common cemetery. Because of the early strong winter the ground is frozen to a good depth. It costs 300 to 500 rubles to have a grave dug.

Mark visited me. He looks bad. Sores have appeared on his face and arms because of starvation. He told me he visited uncle Naum in the hospital. Uncle's heart disease has progressed as a result of dystrophy. He said to Mark, "Let us say our final Farewells."

Again I wrote a report to the Front intelligence unit asking to be accepted as an interpreter in the regular army. It is so cold, my hands and feet are so cold. The barrack has not been heated for a long time.

December 30th

Yesterday I visited the city. The trams were not working. There was no power. In spite of the war some of the theaters were still working. They showed plays not related to war - "Cyrano de Bergerac" and "Dame Kamelias" in the Leninsky Komsomol Theater; 'Three Musketeers' in the Musical Comedy Theatre; and 'An Ideal Husband' in the Radlov's Theater. The majority of theaters are closed.

The Front headquarters representative came again and marked in his notebook that he will assign me to his unit as an interpreter. The cold is about 30 degrees below zero.

|

In 345th Special Radio Intelligence battalion |

Unfortunately that is the last note in my diary. At long last one of my requests was accepted and I was sent to the 345th Special Radio Intelligence battalion. I served for four years (1942 - 1945) in this battalion. My major duty was to listen in to German's battalion and division radio broadcasts. Sometimes they broadcast important messages without coding them during battle. We had to listen to them from the front line trenches because the radius of these radios did not exceed 1 km.

On January 2nd I arrived at the battalion. The battalion commander - Captain Friedman notified me, "There are a lot of young nice girls. Do not flirt with them or you will be discharged." Actually a lot of nice 16-18 year old cute girls were serving there. All of them graduated from radio operator courses and had been mobilized at the beginning of the war.

On January 5th our battalion crossed frozen Ladoga Lake on trucks to the Volkhov Front. We were told, "Be ready to jump to the ice any minute. There are a lot of holes in the ice where a truck could fall through." Thankfully everything ended okay. It was not necessary to jump out of the truck. When we arrived at the opposite side of the lake, I exchanged two packs of cigarettes from my own commander rations for half a kilogram of bread. I couldn't help myself and ate it immediately.

The detailed story about those hard unforgettable years, my friend's death, the war's long wandering road, I will tell next time. It is too long a story for this essay.

| Translated by: | Kirill Finkelshteyn |

| Proofreading: | James Quinn |

The festive firework

|

Josef Finkelshteyn (photo courtesy of K.Finkelshteyn) |

In our area, it was one of the quiet days. The army's newspaper read, 'All Quiet on the Volkhovsky Front', like the Remarque novel 'All Quiet on the Western Front'. One of those usual army days when you think: 'They are shooting, but it is okay. Who knows if I will be hit or not, it depends on fate.'

It was New Year's Eve, 1943. I was serving in the 345th Radio Reconnaissance battalion. The battalion was responsible for tracking German battalion, division and army movements by monitoring radio frequency bearings.

Sergeant Nika Grigoriev, my faithful assistant, and I listened in on German battalion and division radio traffic by using captured radio equipment. Sometimes we were able to catch important messages, because during a battle they often broadcasted in un-coded text. The radio equipment only had a range of one kilometer, so we had to set up near the forward trench line.

Nika and I arrived at the 44th division regiment on the evening of December 29th. When we entered the regiment commander's observation post, we were tired and soiled. 'Help lieutenant Finkelshteyn in his important military mission.', was the headquarters order that I handed to the unshaven, gloomy captain. 'Why the hell did they send you to me?' grumbled the unshaven captain. 'If you loose your head I'll have to write a report - how it happened and why.'

'Find a free dugout. And remember, the ishak (literally 'donkey') bombards our position exactly at 1600 hours every day. But don't show your face from the dugout when it starts to squeak. Yesterday their donkey killed my aid-de-camp and two soldiers. Look at these big fallen trees, that is its work.'

The 'donkey' was the soldiers name for the German truck-mounted multiple rocket launcher, similar to our famous Katyusha. It fired with disgusting squeak 'yya-yya-yya'. Their rocket explosions were very strong.

Nika and I found an un-destroyed dugout partially filled with water. We drained it and laid a floor of spruce branches. It was cold, damp and uncomfortable. We had vodka - the army currency - and I sent Nika to get us a portable stove. One hour later Nika came back empty-handed. Nobody had an additional portable stove.

|

Soviet propagandist. Karelian front. (photo from the Archive of Karelian Front Veterans Board) |

I went to the un-groomed captain, hoping he would help us. In front of his dugout a guard was warming his hands over a portable stove, gladly burning with dry tree branches. Then the 'donkey' started to squeak. Everybody hid as quickly as if a strong winter wind had blown them off. When the guard darted into a dugout, I grabbed the stove and rushed away. Holding the smoking stove with smoldering mittens, I ran as quickly as I could to our dugout. Looking at my watch I thought, 'Sons of a bitches they are so exact'. It was 4:02 p.m.

Nika and I quickly installed the stove, added a few dry branches, and turned on the radio. It grew warm and comfortable. We listened to German news about our Fronts situation while drying our feet. All of a sudden two armed soldiers showed up in our dugout. One of them yelled, 'Hende Hohn! (Russianized German for 'Hands Up!'), do not move!' along with a long sentence full of obscenities which I had often heard my mother use (popravit'). I tried to explain to him who we were and why we were there, but he did not listen to me. He hit me in the chest with his submachine gun and fired into the ceiling, 'If you move you get a bullet in your head bastard! Sergeant, call the captain, we have caught the spies.'

When the captain came he recognized us, and smiling, he said, 'Do not be offended by them lieutenant. Yesterday an SMERSH man told us there was a spy in our division. Whenever our soldiers gather around the field kitchen he sends Jerry a signal and they started to bombard us.' The conflict settled, we invited the captain for a cup of tea. 'Maybe you have something stronger?' asked the captain. Nika took out a flask of vodka and after the third shot we had became best friends.

'Listen to me lieutenant' unshaven captain said, 'Recently people from a propaganda department visited us to shout at the Germans with a megaphone. They forgot the megaphone when they left. Let's curse at the to Fascist bastards in their own foul German language. I will talk and you will translate. I am a foul language specialist'. I tried to explain to him that in school I studied German, but we did not learn obscenities. 'It is okay, just do your best' the captain said. 'Lets go to a closest trench, it is about 100 meters from here.'

Behind the trench there was a ravine with a barbed wire. Germans were on the other side. It was quiet and we were so close we could hear them calling to each other. One was playing their favorite song, 'Lyly Marlen' on a harmonica. 'Lets do it!' said the captain and handed me the megaphone. I could not swear in German as well as the captain could in Russian. But one good turn deserves another, and the Germans replied showing their own good knowledge of Russian foul language. 'These bastards learned enough! I'll teach them a lesson!' said the captain climbed into a nearby friendly bunker and began firing a large caliber machine gun into the German positions. The Germens answered immediately. After short period of time the fire expanded up and down the front. The Germans shot flares on parachutes over our ravine. It grew as bright as noontime.

The regiment commander called us and shouted, 'What the hell is going on?' 'Nothing serious, it is just festive fireworks' answered the captain.

| Translated by: | Kirill Finkelshteyn |

| Proofreading: | James Quinn |

THE VICTORY

May 1945 found me in the Austrian Alps near the city of Gratz. It was spring and sunny, beautiful winter resorts were visible on the snow-covered mountains. Everybody was in high spirits; the war should be over soon.

My Radio Reconnaissance battalion (the 345th) took the bearings of German troop locations and movements. I listened to the daily news from Berlin, London and New York on captured radio equipment and wrote reports for the Front headquarter.

One day I heard on the BBC, 'Sweden's Council-General has announced that Hitler has informed him of his decision to capitulation.' On May 2nd Berlin reported, 'Adolph Hitler has died due to serious wounds. Admiral Donitz has taken command of the German troops.'

Finally, on May 7th, while listening to the American broadcast I heard, 'This is the Voice of America, America at war." this was how all VOA broadcasts during those years began, "Germany has agreed to surrender unconditionally! Tomorrow this decision will be signed!'

That evening I was given the urgent order to exchange this exciting news for wine in the nearby towns. As there was no wine left in the towns behind our lines a driver and myself left for the front. All around us was an unusual silence. The war was no longer working.

In the villages recently evacuated by the Germans there was still plenty of wine. Many of the wine barrels were shot through and half empty. This was the result of our advanced troops wine-tasting. We needed only full barrels. At last we found an undamaged village and went to the nearest house. I told them about Hitler death and tomorrow's German capitulation. The news spread quickly through the village. Soon people filled the room. The burgomaster, a fat man wearied in suede shorts and a green hat with a feather, invited everyone into his house. He told us how he had always loved Russians and hated Hitler. His son, who had been taken prisoner by the British, would now be coming home soon.

We drank dry wine with the Austrian men, some dressed in shorts, some in pants, with both young and old women, attractive and unattractive. Soon all of them seemed pretty to me. Austrians were singing yodels; the driver and me sang the Russian song 'Katyusha'. After a while, swaying, we made our way back to the street. Our truck was full of barrels of wine now. The Austrians helped us climb back into the truck's cabin. I still wonder how we made the drive back to our unit without crashing.

On the night of May 9th the war was officially declared over. Our battalion had a ceremonial dinner. Everybody got one and a half liters of the wine that I had delivered. At least that was the official dose; actually you could drink as much as you wanted. By that evening, no one could safely stand on his own two feet. Guns fired everywhere. Green and red tracer bullets crossed the sky. One could think it was a battle, but it was the peace celebration. The world and all around me were drunk with wine and the knowledge that at long last it was all over. It was the VICTORY!

Austria was a good and beautiful country, but what we really wanted so badly was to go home.

| Translated by: | Kirill Finkelshteyn |

| Proofreading: | James Quinn |