I was born on the 10th of October 1924 in the village of Knyazevka of Arzamas area of Nizhny Novgorod oblast (province).

On Sunday June 22, 1941 I woke up late, at about 10 a.m. Having washed up and eaten brown bread washed down with a mug of tea for breakfast, I made up my mind to go to see my aunt. When I went there I saw her in tears. When asked, she told me that the war had broken out and her husband Pavel had gone to the Military Commissariat to sign up for the Red Army as a volunteer. Hastily bidding farewell I decided not to linger and headed to the dorm of the Gorky River Navigation School where I was a student. On the way by tram I heard people talking about the war and that it wouldn’t last long. “Moska dog attacked an Elephant” – one of the passengers said.

On Tuesday, June 24 I went to the Military Commissariat. The square in front of it was crowded with people. Everybody wanted to get to the Military Commissar. I don’t know how, but I succeeded to find my way into the corridor of the Military Commissariat where a political officer met me. He asked why I was there and I answered that I wanted to go to the front. And having learnt my age he said to me: “You know, lad, go back to school and when the time comes you’ll catch up with the war. You see how many people are here today, so we have somebody to draft”. About one month later I went to the Military Commissariat again. Following my friend’s advice I added two years to my age. I received my medical history card and having passed the medical examination was assigned to the Gorky 2nd Auto-Motorcycle Training School.

We were sent to the station named Iliyno, where after dinner we were informed that we were a part of the 9th Company under the third Motorcycle Battalion. The next day training began. We studied military regulations and practiced marching while singing songs as a whole company. We made dummy rifles out of boards for ourselves. On the 7th of August 1941 we were administered the military oath and it was the first time we bathed and were given summer military uniforms. Presently combat arms were handed to us.

We began our Motorcycle study with models AM-600 with sidecar and IZh-9 and later on, proceeded to study the newly pressed into service M-72. After a few theoretical classes we were taken to the autodrome for driving. At that time bicycles were deemed a luxury and very few boys had easy access to them or were able to ride them. Therefore, they were trained to ride bicycles first and then to ride motorcycles.

The winter of 1941 turned out to be very severe. Frosts in December frequently reached minus 42-45 centigrade. It was so damn cold. Air temperatures in classrooms were not much higher. But while on tactical or shooting classes in the field we could warm up by waltzing; in class we had to sit still listening to an instructor. Furthermore, we were fairly thinly clad: budenovka (pointed cloth helmet), cotton uniform, greatcoat, tarpaulin boots worn over cloth wrapping (puttees), summertime underwear and mittens with one finger (for shooting).

By that time the road from the rail station, snowbound by blizzard, became impassible, which made impossible delivering foodstuffs in December. Therefore, for the whole month our daily ration included two dried morsels of bread instead of the usual seven-hundred grams of bread and five lumps of sugar. Breakfast, lunch and dinner consisted of a bowl of beetroot soup. Anyway, it didn’t hurt our morale for we were sure that those difficulties were temporary.

In late November of 1941 when the Germans approached Moscow, all of the Gorky 2nd Auto-Motorcycle Training School wrote a letter to Commander-in-Chief Stalin requesting that he send us to the front. Just two days later a response telegram from him arrived at the Training School’s address, in which he thanked the whole strength of the Training School for its willingness, but pointed out that the Motherland would need us later and urged us to keep on studying and be better prepared for the upcoming battles. That telegram made us understand that Moscow wouldn’t be surrendered, which was the most important thing. And after a few days our counteroffensive began in earnest.

In March, after eight months of training for motorcycle platoon commanders, the training school released about four hundred people to the front. We, cadets of the 3rd Motorcycle Battalion, were ordered to continue studying, but from that point on we studied the training program for automobile platoon commanders.

We finished the training course for automobilists in June of 1942 and in late July we were sent to the Moscow MARF-3 (Moscow automobile repair factory) for practical training. And after the traineeship we returned to the school and proceeded to prepare for final exams.

In late August, in the middle of the night, the general quarters alarm sounded and all the cadets were sent to the medical unit of the Training School for the next scheduled medical examination board. The selected one hundred men, including myself, were read out the order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief about changing the name of our Training School to the Gorky 2nd Tank Training School. Those who had failed the medical examination board were released as automobile platoon commanders. We, the youth, cheered shouting: “Hurrah!” The elder ones, who fought during the Khalkhin-Gol and the Soviet-Finish wars and/or participated in campaign of liberation (appropriation) of western Ukraine and Belorussia, said to us: “Why are you so cheerful? You will be burning in those iron boxes”. We were already well trained on the automobilist training program, therefore switching to tank study was not a big deal to us.

In the early days of April of 1943 the State Panel arrived to commission the first class of training school graduates. Weapons training and Machinery exams were considered most important and if a person passed them with a “Good” mark he would be conferred the rank of junior-lieutenant, and if passed with an “Excellent” mark, he would be conferred the rank of lieutenant. I passed the Machinery exam with an “Excellent” mark. The weapons training exam was ahead. This training program required firing when a tank stops for a short halt. An “Excellent” mark would be scored if a shot was fired within less than eight seconds, and a “Good” mark for within nine seconds; a “Satisfactory” mark for within ten seconds, and a “Bad” mark if it took any longer. But I, perhaps, was the first in school to start firing while still in motion. At the beginning we had practiced in gun aiming using a primitive swaying simulator which was swung by the cadets themselves. Later on we were sent to a firing range in a farm field equipped with a firing line. A practice target would be tugged by a tractor with a towline about three-hundred meters long. We would fire at range of 1,200-1,500 meters. Everybody feared hitting the tractor. Our battalion commander was a major, a former frontline combatant who had his right arm amputated. He used to teach us: “Stops must be shorter, or better do not stop at all”. When I said to my fellows for the first time that I would fire while still in motion, my company commander tried to dissuade me, but I made up my mind to make the attempt anyway. It worked! I hit the target “tank” at first shot! I was stopped. Company commander Senior-lieutenant Glazkov dashed up to me: “Well, slacker, I’ve told you never..! Suppose what, if you didn’t hit?” He started dressing me down. The battalion commander drove over: “Who fired?” – “Well, the cadet Fadin did, lightheaded”. –“What?! But he did a good job! This is the way, сompany сommander, you should teach the others, firing in motion, like he’s just done!”

And then at the exam I was given permission for firing while still in motion. However, the examiner, a colonel, admonished me: "Bear in mind, if you don’t hit with all three rounds, you won’t even get a junior-lieutenant, but you will get a rank of senior sergeant”. I got into the tank. The driver-mechanic was an experienced instructor. On hearing the “Prepare for action” command I positioned myself at the gun sight. As soon as we reached the firing line the driver said: “Hold on, hold on, there is going to be the “path” soon”. I caught the target in the gun sight, fired – the rear hull of the target was knocked down! The second target “infantry” was also hit. There was a furor! We returned to the starting position. The colonel ran up to me, shook my hand, took off his wristwatch and made a gift of it to me. None of other cadets tried to fire like me, because it was very risky.

On April 25, 1943 I was conferred the rank of lieutenant and early in May we were sent to the 3rd Reserved Tank Regiment, which was based near Factory #112.

Besides myself, the commander, my tank crew consisted of a driver-mechanic, senior sergeant Vasily Dubovitsky, born in 1906, who used to be in 1936 a chauffeur for M. I. Kalinin (when asked what had brought him to us, he answered: “Lieutenant, you’ll find this information in my file”, and added nothing); a gun commander, junior sergeant Golubenko, born in 1925, and a radio operator-machine-gunner, junior sergeant Vasily Voznyuk, an Odessian, born in 1919.

By late May of 1943 the formation of our marching company was nearly finished. Around the 30th of May we received at the factory brand new tanks. We drove them to our firing range where target scenery had been arranged for us. We swiftly deployed in battle order and charged right away with actual firing. At the rendezvous we trimmed ourselves up, and having stretched into a marching column proceeded to loading on the train heading to the front.

At dawn after one night, around the second half of June, the troop train got unloaded at the station named Maryino in Kursk oblast (province). We marched a few kilometers to some grove where we joined the troops of the 207th Battalion under the 22nd Guards Tank Brigade of the Stalingrad 5th Guards Tank Corps, which had been battered in defensive actions.

On the 14th of July just afternoon, having had breakfast and examined the combat vehicles, we were commanded to line up by company ranks. Following the list called out by a battalion staff executive officer, soldiers with combat experience entered our ranks while the newly arrived ones, who had not been in action yet, were removed and sent to reserve. Such reformation changed my position from tank platoon commander to a T-34 tank commander. And the next day, the 12th of July, we went on the offensive.

Three red signal flares soared up. After passing a few hundred meters we saw German tanks pushing forward. Both sides stared firing. Katyusha rockets swished over our heads and German defenses were wrapped in a cloud of dust. There we closed in. I couldn’t imagine that I would find myself in such a senseless, albeit well organized on both sides, slaughter. I feared I might get lost and run over one of the nearby friendly tanks! After firing two shots I was anxious to catch an enemy tank in my gun sight and destroy it. Only in the late afternoon did I manage to hit a German Panzer IV tank, which kindled up right after my hitting it. A bit later I caught in motion an armored personnel carrier with a flag on the right fender and socked at it two explosive-splinter rounds, the explosion of which spread apart with fiery spatters. It worked just fine! Charging forward further, I tried not to break the line of our company. At the end of the 14th of July the Germans fell into an organized retreat and at dusk we captured the town of Chapayev. By dawn there were eighteen out of sixty-five tanks left in the brigade. We washed up, and even though we were not very hungry, had a bite to eat and returned to the battle.

For me the offensive ended on the 16th of July when our tank took two hits and burst into flames. By that time there were four or five serviceable tanks left in the brigade. We were passing along the edge of a sunflower field. Just imagine the picture: the fourth day of the offensive, we had almost no sleep, exhausted … the first round hit a track roller, knocking it out, and the next one flailed the engine. We jumped out and hid in the sunflowers. On the way of returning to our lines I saw four T-34 tanks at the distance of three hundred meters. I was about to go out to them, but the mechanic grabbed my shoulder: “Hold on, lieutenant, do you see crosses on their hulls! Those are the Germans using our tanks”. – “Cripes, that’s true! I bet these tanks are the ones that knocked us down”. We hid, waited until they passed by and walked further. We walked for about an hour and a half and luckily ran into the battalion staff executive officer, who later on would be killed near Kiev: "Good job, lieutenant, I have already recommended you for the title of guardsman”… What did you expect?! Joining the Guards Corps makes a person guardsman?! No! If he could prove his ability to fight in the first battle then the title was awarded to him.

Out of sixty two training school graduates who had come with me to join the corps after four days of offensive only seven remained, and by autumn of 1944 only two of us were left.

We found ourselves in a battalion reserve where for a few days, had a good rest and most important, abundant food. Although, in 1943 we had been fed fairly well, malnutrition, which had accumulated since 1941 and 1942, made itself felt. I saw a cook putting starters into my mess tin and a huge portion of seconds that I had never thought of eating in the peace time. But now my eyes were thinking “go ahead, put some more, I’ll eat it anyway”.

And thereafter preparation for the Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive operation began. I didn’t get a tank, but was appointed the brigade staff liaison officer. I was at war in that position until the 14th of October when I was ordered to take up the tank of the killed-in-action Guards Lieutenant Nikolai Alekseyevich Polyansky. I must say words of appreciation to brigade staff executive officer guards-major Mikhail Petrovich Voshinsky who within two months made of me a map-minded officer, mastering the tasks of a company, battalion and even those of the brigade. Neither a tank commander, nor even a platoon commander or a company commander, without staff work experience, was capable of doing so.

Having found the tank I approached the crew. At that moment the driver-mechanic Vasily Semiletov was digging in the transmission compartment, the others were resting nearby and, as I noticed, all three were scrutinizing me. They were all fairly older than me, but for the gun-loader Golubenko, who was the same age as me and originally had been a member of my first crew. I realized at once that they didn’t like me. “Indeed, they don’t take me as their true commander” – I thought to myself, “Now I need to become one for this crew, otherwise in the next real battle the tank and its crew may perish, or, more likely, the older crew members may malinger to evade battles under any pretext”.

My self confidence developed during my staff work helped me out, and I strictly asked: “What tank is this? Why is the crew resting?” The youngest of them, sergeant Golubenko, rose and reported: “Comrade Lieutenant, the tank crew has finished maintenance work and now is waiting for a new commander”.- "At ease, comrades! Please, everybody, come up to me ". They obeyed, though, reluctantly. They approached me unshaven, carelessly clad, with cigarettes in hands. Holding my hand to my forage cap, I introduced myself and told that I had heard many good things about their late commander, but the crew did not resemble him at all. Then, having passed by the front part of the tank I stopped one meter to the right of it and commanded: “Fall in!”. Everybody stood up, but did not discard the cigarettes. I commanded: “Stop smoking!” They dropped them grudgingly. Stepping out of the line I turned around to face them and told that I was not pleased to go into the battle in such a blotted and dirty tank with an unfamiliar crew. “Obviously I don’t satisfy you either, but as the Motherland requires, I am going to defend it the way I’ve been taught and to the best of my capabilities”. I saw the sneer get off the oldsters’ faces. “Is the machine in serviceable condition?” – I asked. “Yes”, – the mechanic answered, -“but the turret rotation motor failed and we don’t have spare driven track links: all three are guiding ones”. - "OK, we will fight with what we have. Aboard!” They followed the command, more or less. I ascended the tank and told them we would go to the position of the company commanded by Avetisyan. Having taken out the map and consulting it I led the tank to the village of Valky. On the way, at the outskirt of the village of Noviye Petrivtsy we got under artillery fire. So we had to hide the tank behind a stone wall of a building dilapidated by bombardment to await dusk. When the tank was properly parked and the engine shut down I explained to the crew what our destination was and the motives of my maneuver. “You are a good map reader, lieutenant!” –the gun-loader Golubenko spoke out. – “And, apparently, a good tactician, too” - the radio operator Voznyuk said. Only the driver Semiletov was silent. But I realized that the ice had been broken, they believed in me.

As daylight faded we set out and soon, to the accompaniment of the enemy artillery and mortar fire, arrived at the company’s positions. Practically the whole night long, relieving each other in pairs, with two shovels, we dug a trench, extracting up to 30 cubic meters of soil. We put the tank into it and camouflaged it carefully.

Our preparation for charging to Kiev, where our brigade was supposed to go, began on the 2nd of November 1943 when all tank, platoon and company commanders were called to the dugout of the battalion commander. It was fairly dark and fine rain was drizzling. There were thirteen of us and three commanders of self propelled assault guns. Lt. Colonel Molokanov, commanding officer of the brigade political department, assigned the task to the brigade commander very briefly. As far as I understood from his words, the charge would begin the next morning at 8 o’clock.

That night all, except the duty observers, slept tightly. At half past six on the 3rd of November we were invited to have breakfast. When we took breakfast we didn’t want to eat it in the dugout but preferred to stay outside. Not far from us, twenty-five or thirty meters away, preceding the action, our battalion kitchen trailer stationed itself, emitting smoke and steam. As we sat at ease, the enemy opened up artillery fire. I just managed to cry out: “Lie down!” One of the shells fell behind us, some seven to ten meters away, but didn’t hurt anybody with fragments. Another one landed at ten meters from us, did not burst but, tumbling, smashed away a heedless soldier, broke off a wheel of the kitchen trailer, toppled it over together with the cook, torn off a corner of a house and petered out in the gardens on the opposite side of the street. After firing two or three more shells the enemy calmed down. But we didn’t feel like eating breakfast. Having picked up our scarce belongings, we moved into the tank to wait for the charge to start. Our nerves were strung up.

Presently, the artillery raid began and I commanded: “Start up!” and seeing three green signal flares up in the air: “Go forward!” A blanket of smoke and shell bursts were ahead, occasional explosions of short-fallen rounds were seen. The tank jerked heavily – we had passed over the first line of trenches. After awhile I was becoming calm. Suddenly I saw to the left and to the right of the tank running and shooting infantrymen. The tanks running to the right and to the left were firing in motion. Coming down to the gun sight I saw nothing but heaped trees. I commanded to the gun-loader: "Splinter load!” - "Yes, the splinter” – Golubenko clearly answered. I fired the first round at the heaped logs believing that it was the first enemy line. Watching my round burst I calmed down completely feeling like being at a firing range shooting at targets. I was firing at running figures in mouse colored uniforms. I was excited by firing at the figures rushing about and commanded: “Accelerate speed!” There was a forest. Semiletov slowed down abruptly. “Don’t stop!” – “Which way do we go?” – “Go forward, forward!” The old tank engine was growling heavily while we were smashing a few trees one after another. To the right there was the tank of Vanyusha (Ivan) Abashin, my platoon commander, also breaking a tree to move forward. Sticking out of the hatch I saw a narrow clearing passing inward of the forest. I headed the tank over to it.

Ahead to the left, I heard tank guns firing and the reciprocating yapping sound of the fascists’ antitank guns. To the right, I just heard the roar of tank engines but did not see the tanks. My tank was advancing over the forest clearing. “Watch out, boy!” – I thought to myself and opened up gun and machine gun fire in turns along the clearing. It became lighter in the woods and all at once, there was an opening. Seeing the Hitlerites rushing about the opening I fired a round. And at once saw an intensive machine gun and submachine-gun fire delivered from behind the hills on the opposite side of the opening. I caught a glimpse of a group of men between the hills, and all of a sudden – a flash: an antitank gun. I delivered a multiple-round burst from the machine gun and shouted to the gun-loader: “Splinter!” And then we felt a blow and the tank, as if had run against a serious obstacle, stopped for a moment and then moved forward with a sudden pull to the left. Again, like at the firing range, I caught in the gun sight a group of men bustling about the gun and fired a round at them. “The gun and gunners are torn to pieces!” – I heard the cry of Fedya (Feodor) Voznyuk. The mechanic cried out: “Commander, we have our right track broken” - "You and the radio operator, go out through the escape hatch and restore the track! I will cover you with fire”. By that time more tanks and, a bit later, riflemen entered the opening. Track repair with a guiding link (for we had no driven ones) took us about an hour. Besides, while spinning on the left track the tank had been swamped in boggy soil, and ahead to the left, some ten meters away, there was a mine field set by the fascists on the dry part of the opening. Therefore, self extraction of the tank had to be performed backwards, which took about two more hours.

We managed to catch up with our battalion when it was already dark where the Germans had managed to stop our tanks in front of their second line of defense. Through the whole night of the 3rd and early morning of the 4th of November we were refueling and replenishing the machines with ammunition and had little rest. At dawn on the 4th of November the battalion commander gathered all the tank commanders for reconnaissance. Out of the thirteen men who had started the charge twenty four hours before only nine remained. We still had with us three self-propelled assault guns. We approached the trenches of the riflemen and Chumachenko told us: “Do you see over there, three hundred meters away in front of us, complete tree entanglements made of logs?” – “Yes, we see”. – “So, behind these entanglements there is the enemy who won’t let our riflemen rise. Now push forward to this forest edge, line up and attack the enemy”. Why the Germans did not shoot and did not kill us all standing up in front of their defense line, I don’t know.

The tanks entered the forest edge, lined up and charged. We managed to scatter the logs of the entanglements and in pursuit of the Germans through the forest clearings and thickets, before darkness fell came out to the forest edge near the Soviet Farm named “Vinogradar” (Winegrower). There we were faced by a counterattack of up to a battalion of German tanks, including the “Tigers”(Panzer VI). . We had to retreat to the forest and establish defenses. Having reached the forest the German moved forward three medium tanks, while the main forces stretched in two columns and moved into the forest. It was already dark, but anyway they dared to get engaged in a night battle, which they so much hated.

I was ordered to seal up with my tank the central clearing. To the right and a little behind me the tank of Vanyusha Abashin was supposed to cover me, to the left I was covered by an ISU-152 self-propelled assault gun. The enemy reconnaissance patrol, which we had let pass, was advancing deep into the forest. The main forces were approaching. The uproar of engines alerted us that a heavy tank “Tiger” was advancing first.

I commanded to the driver-mechanic Semiletov: “Vasya, at low speed move a little forward, for a tree standing in front of us prevents me from firing at the enemy head-on”. After two days of battles we had forged a good friendship and the crew read my mind at half word. Having improved our position I saw the enemy tank. Without waiting for the driver to bring the tank to stop, I fired the first sub-caliber round at the head tank, which was already at a distance of fifty meters from us. An instantaneous flash at the frontal part of the enemy tank and, all of a sudden, it burst into flames illuminating the whole column. The driver-mechanic cried out: “Commander, damn! Why did you fire? I haven’t closed the hatch yet! Now the gases made me blind”. I had forgotten about everything that moment but the enemy tanks.

Golubenko, before I even turned to him, reported: “The sub-caliber is ready!” Firing the second round I killed the second enemy tank, which was coming out from behind the first burning tank. It also flared up. The forest was illuminated like in broad daylight. I heard Vanyusha Abashin’s tank firing, dull and long sounds to the left of the 152 mm assault gun’s firing. In the gun sight I saw quite a few tanks already on fire. I cried out to the mechanic: “Vasya, move closer to the burning tanks, or the Fritzes (Germans) will flee”. Having approached the first burning tank closely from behind its right side, I saw the next live target, a StuG III assault gun. A shot – and it’s done. We pursued the enemy up to the Soviet Farm of “Vinogradar” where we stopped to trim ourselves up. We refueled the machines with whatever fuel we could find, in preparation for a decisive attack on the city.

On the morning of the 5th of November the Brigade Commander Guards Colonel Koshelev and an executive officer of the political department, Lt. Colonel Molokanov, arrived at our positions. The remaining crews of seven tanks and three self-propelled assault guns paraded in front of their machines. Addressing us, the commanders assigned us the task of capturing the city, adding that the first crews which entered the city would be made the Heroes of the Soviet Union.

About thirty minutes later, having deployed in a combat line, we charged and quickly captured the southern suburb of Pusha-Voditsa, straight off crossed over Svyatoshino, and then the Kiev-Zhitomir Highway. The way was obstructed by an antitank ditch, which had been dug back in 1941, and which had to be passed over to enter the city. Having descended into the ditch the tank stuck: the engine roared at full speed rpm, half a meter long flames escaped from its exhaust pipes, which indicated its extreme worn out state, but it couldn’t get out. To enhance the tractive force, I cried out to the mechanic: “Overpass backwards!” And here is the first street. And here we go again! Because of the guiding track link, with which we had replaced the broken driven one back in the forest, now when we entered the paved streets the tank hull would elevate on the right side with its 10 cm “horn” preventing any gun-firing. We stopped, borrowed a driven track link and proceeded to repair.

The battalion was given the assignment to advance to the center of the city. The head tank had reached a T-junction, and suddenly, ablaze, turned to the right and ran into one of the corner houses. The tank borne reconnaissance party was blown off. Lieutenant Abashin and I opened up firing at a fleeing enemy assault gun. I hit with the second round its rear and stopped its motion. A short halt. The battalion commander strode up to us and assigned the lieutenant Abashin’s tank to be in vanguard. On signal “Forward!” we moved further and shortly entered Kreschatyk Street. The city was captured.

In the evening we were ordered to move out of the city towards the town of Vasilkov. However, while passing over a small river, across its bed, our tank bogged down and due to the worn out state of its engine couldn’t come out. We had to pull it out with a traction engine and evacuate to a repair shop. After a futile seven day effort to revive my tank the repair teams announced that the tank was beyond field repair, adding that I would not be able to continue war with it until 1944. This is how the battles for Kiev ended for me. For those battles the battalion command recommended me and six other commanders for the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union.

In the period of preparation for further battles I was allowed to select people for my new crew, for I had to part with my old one. I don’t mean to brag, but I could tell that people were eager to join my crew. As a matter of fact, I changed nobody in the crew originally assigned to me except for the driver-mechanic. A young boy with surname Kleshevoy (I don’t remember his first name) was the radio operator; a sergeant major of Tungus nationality (whose name I don’t remember either) was a gun commander. A few experienced mechanics of the battalion persuaded me to take Peter Tyurin for the position of driver-mechanic.

On the 27th of December 1943, the brigade was ordered to advance towards villages of Chekovichy, Guta-Dobrynskaya, Kameny Brod and Andreyev. It was the first time that I was entrusted to go in the vanguard machine.

We were heading off to the front line at night. The weather was frosty, soil hard. A thin layer of snow, which had fallen in the morning, slightly silenced rumbling of the tank tracks. Traction with the new tank engine was good and we were moving at high speed. I was nervous because I didn’t know how and where the enemy would meet us. One thought that lulled me was that we were moving across the fields, bypassing populated communities and cutting our way short. Having covered about twenty kilometers we entered a village and stopped. Presently, the brigade formation column caught up with us. We took a very short rest and then we were ordered to move forward. But I had a trouble. My driver-mechanic Peter Tyurin announced that he couldn’t drive any further, because he couldn’t see in the dark. We fussed, for we had nobody to replace him with. The crew members were not cross-trained. Apart from the driver, only I could drive. For about twenty minutes Tyurin was making us worry. Then I felt that he was lying. Had he really gotten blind he would have behaved differently. The guy had just gotten unnerved: it’s not easy moving forward first not knowing what will happen to you the next second. I got angry and raised my voice at him: “Why did you ask me to take you as a crew member?" – And then turned to the deputy battalion commander Arseniyev: “Comrade Guards Senior-lieutenant, please change out Tyurin at the next encampment.” Returning to the driver-mechanic I ordered rudely: “And now go back to the levers and drive the tank!” I commanded: “Forward!” and then strained my eyes trying to see something in the dark through falling snowflakes, communicating the directions through the tank communication device (TPU-10 in Russian). I would often get distracted looking for bearings on the map descending inside the tank lit with a dim light, and after a while I forgot about Peter who was driving the tank with brisk confidence.

At dawn the village named Kameny Brod (Stone Ford) loomed in far distance and closer to me, about five hundred meters away, I saw a dark silhouette, which in the predawn twilight I took for a tank. I fired two armor-piercing rounds at it and saw the sparkles of impact and black fragments spewing out. I realized that I had been mistaken and when we came closer we saw a boulder. Suddenly two Panzer IV tanks rushed out of the village and went fleeing from us to the right, towards the town of Chernyakhovsk. I cried out: “Tyurin, follow them, now”, But he hesitated and stopped. They were already 1.5 – 2 kilometers away. I fired a couple of rounds, but missed. Who the hell cares, we must capture the village.

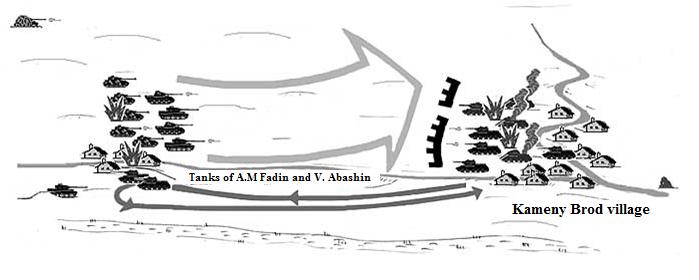

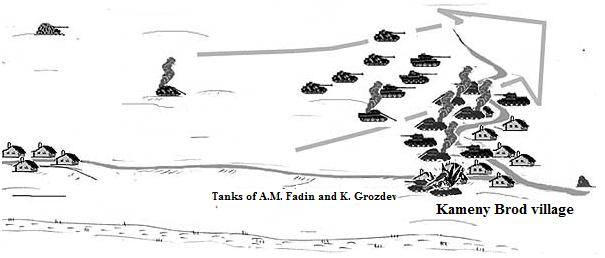

With about three hundred meters left to reach the outermost houses of the village I met an old man who showed me a lane in the mine field and told that there were no Germans in the village, but in the neighboring one there were many German tanks. I thanked the old man and entered the village to cross it along the street towards the opposite outskirt. The houses stood in one line along the road and behind them, to the right and to the left, wide fields were seen. Two more of our tanks, including the tank of the platoon commander Vanyusha Abashin, caught up with me. Reaching the opposite outskirt, I saw at a distance of about one and a half kilometers the neighboring village stretched along the road. Before I got a chance to check its name on the map I saw near the distant village, to the right, the German medium tanks Panzer IV painted in white running on the field. They were followed by “Tiger” (Panzer VI) and “Panther” (Panzer V) tanks, which started coming out from behind the houses and forming into a combat line. I counted seven of them. Behind them the second line of Panzers IV was also being formed, some one and a half dozen. Without hesitation, I commanded: “Armor-piercing load!” – “Armor-piercing is ready”. I fired at the right-flanking “Tiger” – missed! What’s that? I looked at the gun sight – it was knocked off five points to the right. This is why those two tanks had escaped on our way to the village. I verified the gun sight and heard on the radio that the commanders of our and the second company were deploying the tanks in combat order. Sticking out of the turret I saw the entire battalion in the field to the right of the houses deploying into combat order to face the enemy tanks head-on. It was an ignorant decision on the part of the battalion commander, which would be paid for dearly, but I will tell about it further.

|

|

The Battle near the village of Kameny Brod (drawn by S. Kuleshov) |

I don’t know what possessed me, but I decided to attack the Germans. One tank against twenty German tanks! I must have been out of my mind! I commanded to the mechanic: “Charge forward! To that village!” I was followed by the second tank of our platoon, which was commanded by Vanyusha Abashin. To the right of the road I saw a slope to the river; there I could get off the road and stealthy approach the enemy. Once that idea came to my mind, the outermost “Tiger” fired a shot at me from the range of 1 km. It would have killed me, but the solid shot grazed the handle of a plough, which had been left in the field since the autumn and got frozen into soil, and changed its flight trajectory just enough to miss the turret of my tank by a few centimeters. That was luck! Had they fired at me all together they would have made canned mince meat of us. But why didn’t they fire? I cried out to Tyurin: “Turn to the left and move through the low ground along the river to the outermost house of the village!” My pattern was followed by Vanyusha Abashin.

I drove up to the outermost house believing that it had covered me from the German tanks deploying in the field. I was going to peep from around the corner of the house at what the Germans were doing and report to the company commander by radio. I got out of the tank and rushed on the prowl to the corner of the house and was about to stick my nose out when a shell fired by a tank hidden behind a haystack, one and a half kilometers away from the village (evidently to cover deployment of the main forces and support their charge) broke off the corner of that house and cast me back to my tank. I hardly arose for my legs were heavy and I could barely move them. I trudged to my tank, hands trembling. And there, about three or four hundred meters away in front of us, a heavy Panzer-VI “Tiger” of yellow color crept out of a trench. We were standing in the open. Why it didn’t fire? I don’t know … Before I even got into the tank, I cried out to Vanyusha: “Fire, fire at him, f*cker!” But he just stood and stared. Apparently, he was stunned. To be honest with you, I had higher training level than he did, especially after service as a staff liaison officer.

With great effort I got into my tank and aimed the gun at the “Tiger” as it was creeping out. However, as a consequence of the shock and high anxiety I couldn’t accurately calculate the range to it. I made decision to retreat. I commanded to Tyurin to turn around and return to Kameny Brod by the same route we had passed to come here. Having finished deployment the German tanks charged our battalion and fired. Our tanks were burning. I was moving in parallel, some two hundred meters to their right at a speed of 50-60 km/h.

Having overpassed them, I drove the tank behind the outermost house, turned around abruptly and stopped between the house and a barn with a haystack standing nearby. “Now I’ll pick you off firing at your sides.” – I thought to myself. The tanks outflanked the village over the right side and were passing by me. I looked through the gun sight – a pile of manure obstructed the view. I pushed a little forward, turned the turret around and saw that the outermost right-flank enemy “Tiger” passing with its right side to me was ready to fire at one of our tanks standing in its way. I didn’t see my hitting it, but the “Tiger” jerked and stopped, and smoke billowed out of it. The tank of Kostya (Konstantin) Grozdeyev, the 2nd platoon commander, drove over to me. He should have driven behind the other house to open fire, but he huddled up to me. Apparently, the “Tiger” tank, which had covered the Germans deployment from the distance and had fired at me near the neighboring house, fired at his tank. The turret was blown off and it landed onto the roof of the neighboring house. Kostya jumped out… rather his upper body did, the lower body remained in the tank. He scratched on the ground with his hands, eyes blinking. You know?! I cried out to the mechanic: “Back off!” Just as we turned around we felt a blow! Our tank began spinning and stopped on the opposite side of the street. A solid shot had hit the right final drive and torn off a big armored fragment, exposing speed gears, but did not cause serious damage to the tank. The German tanks turned leftwards and swiftly started gathering up to disengage from the battle.

We burned four of their tanks, including a “Tiger”, but our losses totaled up to eight machines, for we had faced them head-on! We should better have hidden behind the houses, let them pass and fired at their sides. Then we would have burned them all down. But it turned out differently. We lost the strength of a company! Primarily, the inexperienced youth, newly arrived for reinforcement. And above all, we let them slip away. Later on we found out that our arrival at Kameny Brod had surrounded that German group, so they undertook the last-ditch onslaught to break through our combat order to escape.

Having regrouped swiftly, the brigade set out in pursuit. It turned dark. The mood was one of disgust: “We’ve lost so many men” – I thought to myself, “Now we must not let them consolidate and take up defenses.

By nine o’clock darkness and drizzling fine rain and snow made me completely blind. The advance slowed down. The other tanks caught up with me. We deployed in combat line and went further looking about at each other. The nightfall attack to nowhere! No sign of the enemy. We started firing explosive-splinter rounds along the path of travel. Presently we passed by a big village.

Not so as you’d notice, day broke and a dirt road appeared ahead. I heard on the radio in plain language text: “Fadin to take up his due position”. I accelerated and projected forward, prepared to act as the vanguard machine. Two more tanks were following me. Dawn exalted my spirit, but not for long. Having stuck breast-high out of the tank I saw through the haze, outlines of a big populated place. I thought that it could be the town of Chernyakhov. Just as I thought so, heavy enemy artillery banged at us.

Deployment and hasty attack began instantaneously. To the left, two hundred meters away from me, a battery of new self-propelled SU-85 assault guns deployed and opened up fire at once. Further to the left a tank destroyer battery of our brigade was deploying. We, by efforts of three tanks, charged, firing at the outermost houses.

I looked through the gun sight and saw a column of tanks advancing perpendicular to us two kilometers away, entering the town from the other side. There was also artillery firing at them and at us from somewhere to the right. A thought ran through my mind that it was a good coordination between the armed forces charging to capture the town. And then I noticed a man in a short white fur coat running from the outermost house towards us. He ran up to the tank destroyer battery commander and punched him in his face. It turned out that the 21st Guards Tank Brigade had already entered the town and we were firing at friendly positions. We took our bearing and headed to the town center. I heard on radio in plain language text: “Fadin and Abashin are to set out for the railway station". I turned leftwards and saw a two-storey stone building of the railway station.

I turned the turret to fire along the street, and suddenly, the tank shuddered with a powerful explosion of a heavy-caliber fragmentation shell, which had hit our right rear flank. The tank continued its motion slowly turning to the right.

|

Driver-mechanic Peter Tyurin, 1945 |

The driver-mechanic cried out: “Commander, they’ve finished off our final drive” - "Can we move?" - "We barely can!" We drove over to the outermost house from the railway station. I got out of the tank to assess the damage. The residue of the armor plate, which used to cover the final drive transmission gear, was as if had been cut off with a knife. Two gears were broken, others had cracks. I still cannot understand how we still could move with such damage. At that moment the battalion commander D. A. Chumachenko drove over in his tank and ordered us to take up defenses and wait for a maintenance party.

We parked the machine in the middle of an apple garden, which was adjacent to the house and pretty soon a mobile maintenance party dispatched by the commander arrived. After a short conversation with the maintenance crew I ordered that the gun commander and the radio operator stay in the tank and watch around. I decided to walk to the railway station building to check out the situation in the town from it. All of a sudden, I heard shouting, submachine-gun bursts and a shot fired by my tank’s gun. I turned around and strode back swiftly. As it turned out, the Germans, who had been left in the rear, endeavored to attack the tank. The maintenance party and the crew took up the defenses. The gun loader fired virtually a pot-shot with a splinter round at the charging infantry. As a result, the Germans lost about ten men dead, the other thirteen surrendered.

The tank repairs took about twenty-four hours and then we had to catch up with our brigade, which had been in action the whole day and night. I can’t remember now when we actually got a chance to sleep. We did it by some fits, one to two hours per day. Fatigue incited apathy, which brought about casualties.

It was already night when we entered the town of Skvira. All were so exhausted that nobody noticed that the New Year 1944 had set in. We managed to take three or four hours for rest. We were waked up by a stick knocking on the turret – the personnel of field kitchen invited us for breakfast. During breakfast we were summoned to the battalion commander. About eleven men gathered near the battalion motor-vehicle with a booth, including three – self-propelled assault gun commanders. There were eight tanks left in the battalion, which was not bad at all, plus two squads of the brigade reconnaissance platoon. Coming out of the booth, the battalion commander, at first, introduced to us the new company commander, a lieutenant-engineer Karabuta, and then he assigned us the task to march to the town of Tarascha, to capture it and hold it until the parent formation of the brigade came.

We started off by daylight. Five reconnoiters and I again had to travel in the vanguard of the column, one to one and a half kilometers ahead. Presently, the "Frame" (Russian nick-name for the German Focke-Wulf Fw189, reconnaissance aircraft) hovered over our heads. It meant that we were going to have company soon. Indeed! Eighteen Ju-87 Stukas showed up. They formed a combat line with intervals of 100-150 meters between aircraft and fell upon us at high speed. The bombing was intensive, but futile: none of the machines got hurt. A small village was ahead, from which we heard firing of field guns and bursts of submachine guns. We were embittered and opened up with return fire putting a small garrison to flight.

We continued advancing in combat order as if something had alerted us that the enemy was near and we would meet him soon. The eighteen aircraft that had finished their bombing and gone were followed by two other groups of eighteen planes in each, which showed up in the distance. They made a big roll and proceeded with their bombing. It proved my assumption that the enemy was very near. Pretty soon, a big village appeared before our eyes. Black against the surrounding white snow, and enormously vast, a continuous enemy column was moving through the village.

The head of the column, which consisted of trucks and horse-teams, had already passed out of the village, picking up speed to slip away. Those appeared to have been withdrawing rear units of the newly arrived enemy 88th infantry division. Seeing virtually a defenseless enemy in front of us, we, firing in motion, broke up the combat order by the width of the column to prevent the escape of even a part of it. Then, unluckily, the populace of the village of Berezyanka came out of their houses to hail us, praying and pleading for us to enter the village quicker, which impeded our firing at the Germans. So, we had to fire over their heads at the Germans, who were fleeing out to the field, leaving their packed wagons and trucks. I was passing along the column, shooting the stampeding Germans with machine guns. Suddenly at the end of the village I saw a group of Fritzes bustling near some wagons, unharnessing horses and driving them aside. I fired a splinter round into their midst, saw them scattered away and only then did I notice a gun which they had tried to manhandle against us right in the middle of the road.

Sticking out of the turret, I saw three more such groups attempting to disengage the horses hauling the guns. I managed to fire three or four rounds, which all landed in the position of that artillery battery. Stopping by the first gun, I ordered Tyurin to bypass it, while firing at gun-crews with a machine gun. When I came back to my senses from the hit-and-run battle, I stuck out of the turret to check out its scenery. It was appalling. Abandoned German wagons and trucks stood along the road, broken and intact, loaded with foodstuffs and munitions. Corpses of killed German men and horses… The same number of dead bodies lying on the snow I would see about a week later in the area of our breaking through the German defense lines near the town of Vinograd (Vine), but those would be the bodies of our infantrymen …

There were about two hundred prisoners of war and we didn’t know what to do with them for we had with us only a reconnaissance platoon mounted on tanks. So, we had to detach from them a few men for their guarding and convoying. We concentrated in the village, appropriating the spoils of war. Tyurin and Kleshevoy brought a big pork carcass each and put them on the transmission bonnet. “We’ll give them to owners of houses where we’ll stay”- they said. And then Tyurin handed me brand new leather officer boots, saying that wearing felt boots all the time was not good, and that boots like those would be never issued to a lieutenant. Yes, the boots appeared to fit me fine and I still remember their strength and impermeability.

Presently the company commander, senior-lieutenant Volodya (Vladimir) Karabuta came up to me and assigned us the task of advancing to the town of Tarascha, which was some ten kilometers west of the village of Berezanka. The frozen dirt road enabled traveling at high speed. After a few kilometers we approached the village of Lesovichy. There were no Germans in it.

There were just about three more kilometers to cover, which we easily did. In twilight, while I was watching through the gun sight, we broke into a street of the town. No inhabitants were seen. It was a bad sign. An ambush might be somewhere. I saw a junction ahead. At that moment a woman ran out of a house and waved a hand. I stopped the tank, stuck out of the hatch and shouted to her, but the uproar of the tank engine silenced her response. I got out of the tank and asked: “What’s the matter?” She shouted that about three hundred meters ahead, at the junction, there were German tanks. I thanked her and headed back to my tank. At that moment the company commander Vladimir Karabuta jumped out of his tank which was following the mine. Hearing my report about the enemy, he said to me: "Fadin, you are, as good as the Hero of the Soviet Union, therefore, I will charge first” – and he started overtaking my tank. I returned to my tank and cried out to Peter Tyurin: “Follow them, and once they are knocked down, overtake them and charge forward!” Tyurin followed. And everything happened exactly as I had said. After passing about one hundred meters, the Karabuta’s tank got a shell at its front and burst into flames. I overtook it and, firing blindly, took the lead. Only then I saw about one hundred meters ahead a heavy self-propelled gun Ferdinand (“Elefant” Sd. Kfz. 184), which resting its rear against a small stone structure, controlled the junction. When I saw the Ferdinand I fired at its front with an armor-piercing round and commanded to Tyurin to ram it. Tyurin approached, rammed the Ferdinand and proceeded to knocking it down. The crew tried to escape, but was scythed by the gun loader’s submachine gun fire. Four of them remained dead atop the hull, only one German managed to escape. I had Tyurin ease up and commanded him to back off. I saw our other tanks and self-propelled guns moving along the street, firing.

I calmed down, mounted reconnoiters on the tanks and moved out to the street leading to the center of the town. Firing ceased and a sort of sinister silence reigned. The company commander and his crew were apparently dead (as it turned out later, he had survived), and we had nobody to command: “Forward!” Someone had to take the lead. And since I was charging first and had executed the Ferdinand so easily, it was my destiny to move on. At the junction I turned left and advanced along the street descending to the river. I approached a bridge and had just thought: “I hope it does not collapse”, when a heavy-duty truck with a big body appeared on the opposite river bank from behind a street turn. In the darkness the Germans didn’t see our tank halted on the opposite river bank at the bridge foundation, so they moved across the bridge and almost butted with their bumper against frontal part of our tank. The driver reacted quickly and jumped out of the cab, right over the side of the bridge. I only had to pull the gun trigger and an explosive-splinter round pierced the cab, exploding inside the body packed with Germans. Fireworks! I said: “Petya, forward!” We pushed the wreckage of the truck’s front and engine off the bridge, ran over the dead bodies on the bridge and went up the street. The reconnoiters jumped off the tank near the bridge, and evidently went to pick up booty – wrist watches, pistols. Wrist watches were very rare then. Even a tank commander had only a cabin clock with big face.

We moved on slowly, made a turn and, firing a round along the street, sped up towards the center of the town. We approached a T-junction. I parked the tank in a shadow against a wall of the house constituting the cross-bar of that “T”. Neither Germans, nor our tanks were seen. We shut down the engine, lurked and watched out. It was kind of spooky to advance in the night along moonlit streets without reconnoiters and a tank-borne party and standing idle was also unnerving. A grisly silence was all around. Suddenly I heard a sound of a few tank engines, and instantaneously three our tanks ran past me at high speed along the street. Sounds of explosions and gun firing came right from the direction where they had just gone. A battle broke out in the eastern outskirts of the town where the bulk strength of the brigade had been concentrated. I waited. Presently the sounds of battle form the direction where the three tanks had gone died out. They might have been burned down.

About 15-20 minutes later I heard a sound of a German tank coming from there. I decided to let it approach close by and destroy at range of a hundred meters. Suddenly, a silly idea occurred to me. I wanted to destroy it nicely, with style and then to write with chalk on its hull: “Lieutenant Fadin knocked it down”. What a folly! To make it happen I should have let it reach the junction, i.e. to the range of 15-20 meters from me, and sock an armor-piercing round at its side when it turned left (somehow I was sure that it would turn to the left street). So I aimed the gun at the enemy tank. The tank was not big: Panzer III or Panzer IV. It reached the junction, turned left. I started rotating the turret to the right…. but it didn’t go. The enemy tank made a pass along the street. I cried out to Tyurin: “Start up and enter that street, we will fire at its back!" But the tank didn’t start up at once. We missed them! I jumped out from the turret hatch to the tank rear. Tarpaulin had been fitted to the back of the turret. The reconnoiters, who sat behind the turret, would stretch it out to bed on the cold armor. A dangled edge of tarpaulin had got under the gears of the turret traversing mechanism and jammed it. There was no way that it could ever get there, just couldn’t!!! I still cannot let go of the thought that I had missed that tank! After the war I told this story to my mother. I said: “The tarpaulin just couldn’t get stuck under the turret”. At that she answered to me: “How many times did the God save you? 4 times. The God is one for all. There might have been righteous people in that tank. So, He did stick the tarpaulin under your turret ".

Having extracted the tarpaulin and jumped into the tank, I ordered to Tyurin to come out to the street along which the tank had gone, hoping to catch it by firing a shell. At that moment I heard on the radio: “Fadin, Fadin, come back urgently!” I turned about the tank and set out backwards to the bridge. Apparently, the battle was abating. Having incurred casualties, the Germans began withdrawing their units. This is how on the night of the 4th and the early hours of the 5th of January we liberated the town of Tarascha.

Before noon on the 5th of January we were trimming ourselves up and slept a little. At 1400 hours of the 5th of January 1944 we began advancing across the whole town westward to the town of Lysaya Gora (Bald Mountain). As before, four reconnoiters were mounted on my tank and we took the lead in the vanguard of the column.

We entered the suburb of Lysaya Gora. To the right I saw white Ukrainian huts and a forest ahead blackening against the white snow. I commanded to Tyurin to accelerate. Rushing across the streets of Lysaya Gora my left side took three or four shells fired by a semi-automatic gun. The tank drooped to the right in some pit, so, the only way we could fire was airwards. We stopped and I opened the hatch, got out of the tank and saw that my left final drive was broken. The tank was no longer capable to take a turn to improve firing position, let alone further movement. The battalion commander stopped by and ordered us to wait for a maintenance party, leaving a squad of riflemen with their commander to guard us.

Leaving the guard post, we took the pork carcass, which we had captured from the overrun wagon train and since then carried on the tank, aroused a house owner, an old man named Ivan, and his wife and asked them to fry us up some pork. We had a good supper. But we couldn’t fall asleep. We started preparing for the defense of our knocked down tank. For that purpose we took off from the tank the coaxial machine gun and the machine gun of the radio operator, prepared grenades and a submachine gun. Seven riflemen and their commander joined our effort. So, we had enough strength to repel an attack of the enemy infantry. At dawn we made an all-around defense and I waited for the Fascists’ attempts to capture our tank. At about nine o’clock in the morning four locals came and told us that the Germans, a group of twenty men or more, were approaching to attack us. I sent the locals away to avoid extra casualties, and we took cover and prepared for a battle.

Literally three or four minutes later the Germans wearing white camouflage suits (parka) with submachine guns in a disorderly group, almost a crowd, showed up from behind the houses and headed towards us. Upon my command we opened up concentrated intense fire at them and killed, apparently, ten men. They took cover on the ground and then carried away their casualties and did not disturb us anymore. By 1400 hours the main forces of the brigade arrived, which had defeated the Germans opposing us, left a mobile maintenance party and took away my infantry, and then moved towards the town of Medvin after our battalion.

From the 6th to the 9th of January 1944 the maintenance teams were restoring my tank making it operational and ready for action. We amused ourselves by talking to the local beauties living in the neighborhood. At nights we gathered together and talked about our childhoods or played cards. On the morning of the 9th of January the battalion commander Dmitry Chumachenko arrived. He praised my performance in the town of Tarascha and ordered that when the repairs were finished I should take command of a half-company of tanks, returning from maintenance like mine, and lead them to liberate a village, located a few kilometers away from the town of Vinograd, and we did it.

Sometime around the 17th of January we were ordered to hand over a few of the surviving tanks to the 20th Guards Tank Brigade under our Corps and withdraw to the corps reserve to reinforce it with tank crews arriving from the rear. We were being resupplied and replenished near the town of Medvin for just a few days. For the first time since the last resupply in November the officers of the brigade got together. We were short many men. Of course, the first to die were the newly arrived crews with marching companies, who were poorly trained during team building in the rear. The brigade incurred the highest casualties during the first battles after resupply. Those who survived the first battles got accustomed quickly and then constituted a skeleton of the units.

During the period of resupply I was appointed the battalion commander's tank commander. The crew was manned by very experienced tankers, who had been at war for a year, if not more: driver-mechanic, Sergeant major Peter Doroshenko, decorated with the Orders of the Patriotic War of the 1st Class and the 2nd Class and the Order of the Red Star, the gun commander, Guards Sergeant Fetisov, decorated with two medals “For Courage” and the radio operator, Guards Sergeant Elsukov, decorated with the Order of the Patriotic War of the 2nd Class and the Order of the Red Star. Besides, all they were decorated with the medals “For the Defense of Stalingrad”. Even then in 1944 when practice of decoration became more frequent, those were very highly-valued decorations and such a crew was the only one in the brigade. The crew lived separately and it didn’t keep company with the other thirty crews and when after announcing the order I arrived at the house where they had been billeted, the meeting was suspicious. Indeed, it was not easy for them to accept me as their superior since I was the youngest lieutenant of the brigade with only the experience of the previous three to four months of battles; besides, Peter Doroshenko and Elsukov were much older than me. I also realized that I had yet to prove my right to command those people.

As early as the 24th of January the brigade was engaged in the breakthrough, which had been breached by the 5th mechanized corps towards the town of Vinograd. Engagement in combat was performed at dawn virtually by leapfrog over the riflemen of the 5th mechanized corps, who had just attacked the enemy. The whole field in front of the German defense line was sown thick with the corpses of our soldiers. How come?! It was not the year 1941 or 1942 when there had been shortage of shells and artillery to suppress the enemy firing points! Instead of an onslaught we were crawling on the plowed land, bypassing or leaving to the right or to the left of our tank tracks the corpses of our soldiers as not to run them over. Having passed the first line of riflemen, we abruptly, without command, accelerated the charge and quickly captured the town of Vinograd.

Sometime in the morning of the 26th of January the battalion commander was given the order to hand over his tank with its crew at the disposal of the brigade commander, Guards Colonel Feodor Andreyevich Zhilin, who had lost his tank during the January battles. This is how in the last days of January 1944 I became the 22nd Tank Brigade Commander’s tank commander.

Being at war in spring of 1944 in Ukraine was a complete torment. Early thaw, drizzling wet snow turned roads to marshes. Ammunition, fuel and foodstuff were supplied by horses, since all the vehicles were stuck. Tanks moved somehow, but the motorized rifle battalion straggled behind. We had to ask help from citizens – women and teenagers – who from village to village carried on their shoulders a shell each; or a cartridge box in pairs, sinking to their knees in the mud.

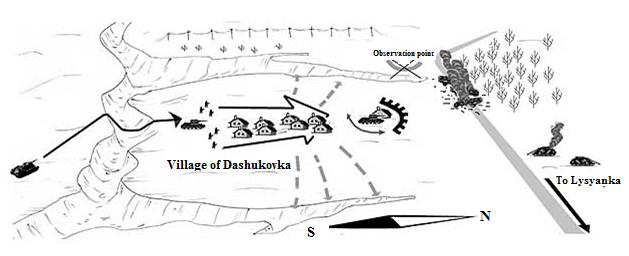

At the end of January, while surrounding the enemy Korsun-Shevchenko Army Group, we were ourselves encircled and barely escaped, sinking eight tanks in the river of Gorny Tikich. Then we were repelling attacks of the Fascists attempting to break out. In short, by the 18th of February, when we were ordered to concentrate near the village of Dashukovka, the brigade commander’s tank – my tank and a motorized rifle battalion of submachine-gunners were the only ones that had survived in the brigade. For real, the battalion had only 60-80 men left and two 76 mm guns, which had straggled behind bogging down in the mud. The brigade command was concentrated in a village located not far from Dashukovka. The motorized riflemen were due to arrive in 5-6 hours. The enemy had just forced our troops out of Dashukovka, thereby virtually breaking the encirclement. The brigade commander, the political department commanding officer and I drove up to a deep ravine, which severed us from Dashukovka, which was in distance of 1 km from us. The village stood on a hill stretching from north to south with a street about one and a half to two kilometers long. It was surrounded on three sides with ravines and only the northern, the furthermost from us, had a flat slope for a dirt road coming from the village of Lysyanka. An inactive battle was ongoing near the village. Apparently, both belligerents were extremely exhausted, with no reinforcements. From time to time the enemy’s six-barrel mortar (“Nebelwerfer”) would cast bombs somewhere from the northern outskirts of Dashukovka towards our infantry. We returned to the village standing in front of the ravine.

Having parked our tank near the house selected by the brigade commander, I entered it to warm up and have my soaked boots dried out. When I entered the house I heard a radio conversation between the brigade commander and the corps commander, the Hero of the Soviet Union general Alexeyev: “Zhilin, seal up the gap!” – “But we’ve got only one tank left”. – “So, seal it up with that tank!” After the conversation was over, he turned to me: “Did you hear, son?”

The task was clear; To back up the infantry of the 242nd Rifle Regiment that had abandoned Dashukovka thirty minutes before, and thereby opened a 3 kilometer gap, to capture Dashukovka, reach its northern outskirt and prevent the approach and breakthrough of the enemy to the surrounded ones over the only dirt road passing 500-600 meters to the north of Dashukovka until the corps reserve arrived.

|

|

The battle of the village of Dashukovka (drawn by S. Kuleshov) |

I swiftly left the house. My crew members were impassively chewing bread and spam stew. The lady of the house followed me from the house with a jug of milk and offered it for me to drink. But I was so angry at the world. I didn’t know what was going on in Dashukovka, what the enemy strength was there, and how to force them out.

I cried out to the crew: “Prepare for action!” They looked at me bewildered first, letting off a couple of jokes about my zeal, but seeing that I was not joking, put aside their food and all dashed to the tank. I ordered them to discard the tarpaulin to avoid repeating the mishap which had occurred in Tarascha, to take out of the tank everything unnecessary for battle and to resupply ammunition. Thus, I was going to the battle with a double allotment of rounds: one hundred and fifty instead of the usual seventy seven. Within twenty minutes the tank was prepared for the battle. The whole command came to see us off. I waved to all, stood up on the seat and putting my hands on the commander’s hatch, commanded: “Forward!”

For the first time, since I could remember, I didn’t feel sick at heart as I had always felt prior to the attack before the first shot was fired. The last parting words of political department commanding officer Nikolai Vasiliyevich Molokanov: “It must be done, Sasha!” – cheered me up.

Reaching the curve of the ravine, which offered the shortest route to the village of Dashukovka, we started descending slowly down its slope. There was only one way: to pass over the ravine and launch an attack against the southern outskirt of Dashukovka. We rolled down easily, but we failed to ascend to the opposite side. Reaching an impasse half-way up the opposite slope, the tank rapidly rolled down to the ravine bottom. We made a few attempts to ascend, but every time the tank would fall down. As it turned darker an ice crust appeared on the ground, which made our ascending task even more difficult. Exhausted, I remembered how we had passed over the ditch near Kiev using the reverse gear. We found twelve caterpillar track spikes in SPTA (spare parts, tools & accessories) and attached six of them per each track. We finished with that within a half an hour, turned about the tank for its rear motion and all three of us: the gun-loader, the radio operator-machine-gunner and I grabbed the bulge of the frontal armor plate and started pushing the tank upwards. We were so heavily exhausted that did not realize that our effort for a twenty-eight ton machine was nothing! And had the tank rolled down again, it would have killed us all. Nevertheless, our anger, will, the driver-mechanic’s skills and the attached spikes did their job. Roaring with strain, the tank slowly but surely was crawling up. It seemed that it would stop any moment, and we with all might pushed it up striving to help the engine. Elevating its rear over the edge of the ravine, the tank froze for a moment, but clinging to the ground rolled over to the opposite side. Finding the way up, the mechanic started turning the machine around. A pall of fatigue veiled my senses. Hearing the noise of the running engine, the Germans began launching illuminating flares. Rifle and machine gun fire intensified. Taking a look around, I commanded to the crew: “Aboard!” and gave direction to give a half an hour`s rest to the tank. Having closed the hatch I sank right away into oblivion. Apparently the same happened to the rest of the crew.

A loud knock on the turret pulled me back from the oblivion. I asked who was there. The commander of the 242nd Rifle Regiment responded to me. I opened the hatch and introduced myself. He complemented my successful passing over such a deep ravine and talked business: “Look, over there are moving lights. Those are the German motor-vehicles passing. I think that a number of enemy units have already passed on this road. At this sector we’ve gathered the remainder of my regiment – about a company strong. You must, under cover of darkness, support my infantry’s attack, reach the northern outskirt and seal up the road with your fire. A motorized rifle battalion of your brigade is on the way, so the help is near ".

I saw flickering cigarette lights about two hundred meters ahead; it was the infantry lying on the wet snow. I ordered to the mechanic to approach the infantry and commanded: “Prepare for action!” I showed to the gun loader a stretched out palm – “Splinter!”

Stopping the tank at a ten meter distance from the riflemen, I looked at the soldiers armed with rifles lying on the snow. Only a few of them were armed with submachine guns. Apparently, they had been scratched together from all the regiment units. I took a glance to evaluate their number and saw in a line 300-400 meters long about fifty men. Sticking out of the commander’s hatch I addressed them: “Guys, now we are going to fight the enemy out of the village and reach its opposite outskirt, where we’ll take up defenses. Therefore, don’t lose your shovels in the battle. Now you in short bounds advance in front of the tank about 20-25 meters ahead and shoot at the enemy on foot. Don’t be scared of my firing because I’ll be firing over your heads!” One of them cried out to me: “Since when do the tanks charge in the wake of the infantry?” I said that the question was fair.. “But today we have to act this way. I will be destroying the enemy firing points and once we come to a distance of two hundred meters from the village I will take the lead, and you will throw in behind me. Now look around and on my command charge forward!” The engine roared up. The Germans launched a few flares and seven machine gun points started working right away. I switched the gun sight for night time firing and began picking them off from right to left. Within one and a half to two minutes my rounds suppressed three or four firing points at once. I stuck out of the tank and commanded: “Forward!” Seeing my marksmanship, the infantry rose, hesitantly first, but went on the attack. The enemy opened up firing again from four or five points. I picked off three more of them and commanded to the mechanic to move 25-30 more meters forward, firing two rounds at the village outskirt. Moving slowly, I destroyed one more firing point. I saw from the tank my infantry moving forward in short bounds. The enemy fired only rifles. Evidently, the Germans capturing the village, left there a small covering force, up to one platoon strong, and did not even have an antitank gun, throwing the major forces to the surrounded ones for breakthrough. It was a decisive moment – seeing how I had killed the firing points, the infantry believed in me, continued with bounds, firing on foot and from the ground. It was such a favorable moment, which could not be wasted. Therefore, I stuck out of the tank and cried out: “Well done guys, and now charge!” Taking over their line and firing in motion I broke into the village. I halted for a moment, fired two gun rounds along the street at fleeing Germans and a multiple-round burst from the machine gun. I saw some structure attempting to turn itself out from a house yard to the street. Off-hand, I cried out to Peter: “Crush it!” The mechanic jerked the tank forward, knocking that big monster with the right side, which eventually appeared to be the six-barrel mortar.

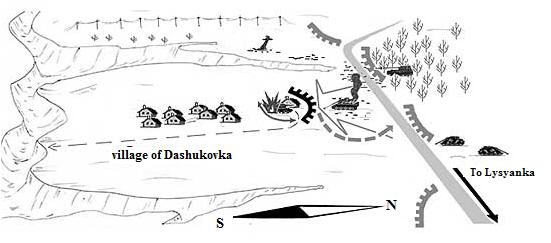

We continued the advance, shooting the Germans running out of houses and rushing about vehicles. Many of them managed to come down to the ravine and escape, but those who were running along the street because of fear of the dark or obscurity of the ravines, would receive their due bullet. Presently, reaching the northern outskirt I began contemplating picking out a good position for defense. About two hundred meters away from the main bulk of houses, a solitary hut was standing. I drove my tank up to it and parked with its left side against the house wall. Ahead, about eight hundred meters away, single vehicles were passing along the road. The mission was accomplished – the road was at gun point.

By that time my infantry began coming up to me. About two dozen of them remained. I commanded them to take up an all-around defense, because the enemy might have outflanked us through the ravines and dug in. As I had thought, the infantrymen had no shovels and they were huddling around my tank looking for protection. Seeing that, I recommended all to disperse taking comfortable defensive positions and to be prepared to repel the enemy counterattack at daybreak. A few minutes later, from behind a grove which grew to the left across the road, a whole town of light came forward – a column of motor-vehicles carrying infantry with their lights on (the Germans had traveled at night with their lights on throughout the whole war). I determined through the gun sight the travel speed – about 40 km/h and waited for them to come out right in front of our defenses. I had not expected such a bounty from the Fascists. I determined the range, made allowance for the lead vehicle. In the blink of an eye my round turned its body into a fireball. I turned the gun sight to the last vehicle in the column (the eleventh), which after my shot hopped up and, bursting into flame, fell apart. A panic began on the road. An armored personnel carrier, travelling second in the column, rushed out to bypass the burning lead vehicle and got stuck with its bottom in mud. Other vehicles attempted to pull off the road to the right and to the left but immediately got bogged down in mud. My third round, which was fired no more than six or eight seconds after the first one, set the armored personnel carrier on fire. My mechanic told me: “Lieutenant, don’t destroy all the vehicles, we will take booty from them”. “Alright”. The place was lit like in broad daylight. Running figures of the fascists were seen in the glare of the fires. I fired at them a few more splinter rounds and firing in short bursts, emptied one of the coaxial Degtyaryov machine gun’s pan magazines.

Gradually the night yielded up to dawn. It was foggy and a fine albeit wet snow was falling. The enemy did not counterattack, but was just extracting the wounded from the battlefield. My infantrymen were pinched with cold and did whatever they could to warm up. Some of them went to the outermost huts to warm up.

The crew continued their watch. Experienced combatants, they realized that soon the Germans would fall upon us to force us out. Indeed, presently a young soldier came up to the tank and cried out to me: “Comrade Lieutenant, the enemy tanks!” I tried to open the hatch to look around, but before raising my head above it felt a bang of bullet on the hatch lead, a tiny fragment chipped off the armor and scratched my neck. I closed the hatch and started looking through triplexes to the direction pointed to me by the soldier. To the right, one and a half kilometers away, roundabout, two Panzer-IV tanks were stealthy creeping on the field: "Here it starts!"

I commanded the infantry and my crew to: “Prepare for action!” I ordered loading a splinter round because the tanks were far and I needed an adjustment fire. The round exploded five to ten meters from the leading tank. The tank stopped. I socked the second round at its side. The second tank made an attempt to leave, but after the second round it stopped and one of the crew members jumped out of the turret and ran into the field.

The early morning of the 19th of January 1944 was good; I relaxed and almost paid for it: a bullet banged at the hatch edge when I tried to open it to look around. The soldier, who had pointed out the tanks to me, came up and told me that to the left behind the ravine some German officers were looking at our positions through binoculars. Having said that, he turned around to leave, but suddenly, shook and fell on his back. Looking through the triplex I saw blood trickling from the back of his head. I cried out asking to take his body away and ordered to the mechanic: “Petya, back up the tank and bypass the house in reverse gear in anticipation of returning here”. In reverse, the tank slowly crawled out from behind the house. I turned the turret around and through the gun sight saw four figures lying on the snow right behind the ravine, about four hundred meters away from me. Those might have been a group of officers with a general, a collar of his greatcoat was mounted with fox-fur, reconnoitering the ground and my position. I cried out: “Fetisov, Splinter round!”. Fetisov unscrewed a cap and reported: “The splinter is ready!” I aimed, and the round exploded right in the middle of that group. At once I saw at least fifty figures in white camouflage suits rushing in from everywhere to rescue the wounded. And then I avenged the young soldier, firing fifteen splinter rounds at them. “Quieting” the Germans this way, we returned to our position (to the right side of the house) and awaited further activity from the enemy. The radio was silent to our callings. We had only fourteen rounds left, including one sub-caliber, one armor-piercing and twelve splinter ones, in addition to one incomplete machine gun pan magazine for each, Elsukov and me.