I was born on November 7th, 1920, in a peasant's family, in the Voronezh (now Lipetsk) oblast . My father, an NCO of the Tsar's army, during the Civil War commanded the mounted reconnaissance unit of 1st Cavalry Army's 14th Infantry Division. Nonetheless, his officer's past affected both his destiny and my own.

In 1931, I finished 4th Grade. In May, my father was arrested and convicted of, as it was then customarily put, "officer-like gentility." Later, after two years of imprisonment, he was released. I, until 1934, was in an orphanage. That year, all sorts of schools began expanding and I was assigned to a vocational school at a factory. After a year there, I applied to the newly opened college of political education which was located straight across from our local high school. At the college, we were trained as commissars (political instructors) and I was admitted to Komsomol (The Union of Young Communists) - they did not accept peasants as full members back then and gave one year of probation. In 1937, the country was swept with the call: "Let's Get 300,000 Pilots for the Country!" The local Komsomol branch decided to send several people, including myself, to the Leningrad Lenin's Komsomol Pilot School. I wasn't accepted. I tried to apply to another one, but they wouldn't accept me either. Wherever I went they would just told me "The admission is over." Now I understand that somewhere in my application papers, there was a little special stamp, which I never noticed, that revealed my parentage. The situation was desperate: I ran out of money and slept in a shed I stumbled upon in the Summer Gardens of the Mars Fields Park.

All of a sudden, in one of the schools, a colonel, to whom I was speaking, asked me to come next day to the Mikhailov Castle. I went. I was met by Colonel Zlatogorski and, after a conversation, I was enlisted in the Zhdanov Military-Engineering School. We were taught very well. While at the school, I was made a candidate member of the Party and assigned an acting platoon commander.

It must be said that 1937 through 1939 were the years of mass persecutions of the officers corps, when a disheartening eradication of military commanders was taking place. There was not a single lieutenant in the entire school! They had to pick platoon commanders from among us, ignoramuses!

Thus I graduated from the school. We had a commencement ceremony; the next morning there was an official meeting. We got together. I was sitting in the second row. An engineer, 2nd class, comes out in the front and begins telling us about new weapons. On the table behind him, we see two huge covers. He told us about the new tanks, airplanes, other things:. At the end, he says: "And we also have this:.. " and takes out an SVT rifle. It is such and such and such. He turned it around in his hands and put it back in the sheath. Next, he pulls out a PPD submachine gun from underneath the other cover. Turned it around, said a little and put it back. Thus, our introduction to the new weaponry was finished.

I was given the rank of Lieutenant and sent as a platoon commander to the Rybachi Peninsula. There were only eight of us, Party candidates, among the 200 graduates and we all were promised assignments in the Far East. It was so popular then! We had just gone through Khasan and Khalkin-Gol! But those seven went there without me. I was very upset. I didn't understand it then - it was all because of my father. Anyway, thanks to the efforts of the battalion commander who spoke about me with school commander Vorobiev, my assignment was changed and I went to Kandalaksha instead. At the very least, it was a town. I arrived to Kandalaksha on September 9th, 1939 and was immediately assigned a platoon commander of 16th Special Engineers Battalion, 54th Rifle Division. At the time, the situation was already very tense there. I, of course, did not understand anything but everybody was talking about war. We began training. That's where I showed off on skis -- I was a good cross-country skier.

On the 5th of November we turned in all of our equipment and, as if in a drill, were put on a train and shipped down south. Instead of training camps, we arrived to Station Kochkana, in the vicinity of Belomorsk. From there, on skis, we advanced to the border, toward Reboly. We skied for about 40 kilometers. On the way, we learned how to deploy, take positions, organize reconnaissance. Later, trucks arrived. We loaded and continued on to Reboly. That's where we waited for the war to begin. In the meantime, we were getting to know the border guards. They organized meetings for us, told us about the specifics of the local terrain. We didn't know anything about the Finnish arms, Finnish mines, never saw any Finnish clothing. I, and many others, had always thought about the borderline as a huge, sky-high wooden fence. I was taught a great deal by the "elderlies" of my platoon - Andrei Khlushchin, Pavel Rachev, Melnikov, Remshu, Mikkonen. They were 40-45 years old and called me "sonny."

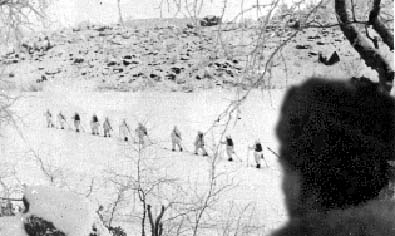

About two days before the offensive, we were ordered to assemble recon groups to be made of skiers. I selected 42 men who could ski. Those were primarily Karelians, Finns, Veps, Siberian hunters. As a commander of this unit, I fought through the Finnish War.

So, when at 6:00 on the 30th of November, I approached the borderline near Post 661, I was asking the border guards who led us to the first farmstead:

- Hey, where's the fence?

- What are you talking about? There's this trail here and that's it.

The first farm was taken easily. We proceeded further. Then took the second farm. While taking the third farm, we surrounded them and beat the hell out of them! In that battle, I was shooting from the kneeling position, near a tree. A projectile hit right in the pointed top of my helmet. I was pushed with such force that I fell on the ground. So, there I am, lying and thinking: "What's going on? I am lying here, my soldiers see me lying?" It was thought then that the commander must be running headfirst in a frontal assault, yelling: "Hurra! Forward!" and so on and so forth.

With combat, we were moving forward and I must say that we could go as far as Kuhmo but we were ordered to halt and take defense positions. That's how we got surrounded. The division found itself in two pockets: 337 Regiment and our 16th Engineers Battalion - within the first ring; two rifle regiments, artillery regiment, tank battalion, reconnaissance battalion and HQs - in the second ring, - in a mere 9 kilometres from us. The 5th Border Guards Regiment blocked the gaps between our positions with two blockhouses. They, however, were subsequently wiped out by the Finns.

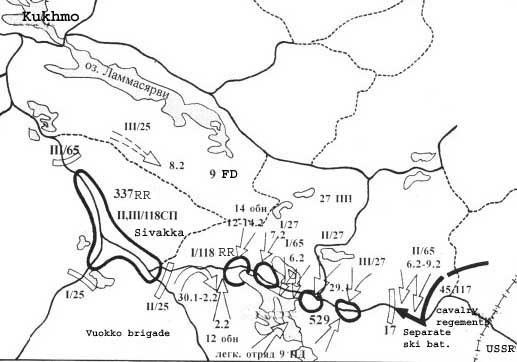

|

Map of 54th RD actions 29.01 - 6.02. 1940 |

We advanced. We had to deploy so that our positions at least could not be cross-fired by the enemy's machine guns. I, a green lieutenant, couldn't understand that but our battalion commander Kurkin was an experienced officer. That was how he put it: "A machine gun here, a machine gun there - lest we be cross-fired." We spread the companies and dug three rows of trenches. The trenches were covered three layers of logs. We made dugouts for ourselves and covered them with three layers of logs, too. Then we laid up minefields and set up barbed wire obstacles. We had two anti-aircraft quad-guns. The Finns didn't have any air force - throughout the whole war we saw their planes flying above only three times. These quad-guns got installed in trenches in front of wide-open spaces. Those guns just cut the infantry to hell! After several attempts, the Finns forgot how to walk in an open space - they only moved in the woods. We established a good communication link with Major Churilov's 337th Rifle Regiment. In short, we set up our defenses in the most proper way! And that's why we managed to hold.. An important part, of course, was a good rapport with the border guards who knew both the land and the Finns well. We were fortunate when Colonel Dolin's Ski Brigade came to our help. They were used very cleverly - they held the road and took care of retrieving the wounded and ammunition supplies. At that time, however, nobody could get through to us. Food and ammunitions were dropped from the planes. Only once four trucks with food and two regimental guns succeeded in breaking through to us.

|

Those were heavy, difficult fights. The infantry did not have skis. So, the troops could move only by road. Until mid-January, we were fighting with pain! Everything was to be learned in combat. Learning in combat means losing people. It must be said - our experience was earned through a lot of blood. Only in my unit, I practically had to replace everybody. There were only Murzich, Mikkonen, Remsha, Khluchin, Pelekh, Diki and one other guy left, that's it. I had 18 people killed in my unit.

We didn't know Finnish landmines - we would stumble upon one of them and study it, until somebody gets blown to pieces. Sometimes we were just lucky. The Finns used English-made anti-personnel mines, the ones they later started making themselves. Besides, they also put artillery projectiles right into field obstacles. Fields in front of wire obstacles were also densely mined, they put mines right into snow, set up booby-traps. The mining density was very high. Doors in villages were also booby-trapped. At first, our scouts were getting blown up. But, come January, we began fighting differently. In late January, we had a second unit formed in our battalion. We also acquired some kind of sense for these mines. When you look at the snow at first, you see only an even surface, but after a while you discern little bumps. You look in your binoculars, then send in the scouts - indeed, landmines are there.

- A. D. How often did you on reconnaissance missions?

We went every night. The objective number one was to capture "a tongue." The thing was that the Finns removed all civilians from the battle zone. During the whole time, we met resistance only at one of the hamlets where a man and a young woman opened rifle fire. We surrounded the house and, via an interpreter, offered to surrender, otherwise, we said the house would be burned down. They did surrender. We brought them back. I was later told that the girl turned out to be a member of the Lotta organization and was executed.

We walked into a house in one settlement and saw Lenin's portrait on the wall. Well, we thought, a communist lived here! Later somebody explained to me that Lenin was held in respect for the liberation of Finland [from the Russian empire], of which I did not know. We checked out the cellar - there was meat, liqueur, vegetables. Typically, the cellars were full of stuff in any Finnish house but we weren't allowed to take anything. I could take some potatoes but it was forbidden, too. Our rations were pretty meager -- four men were issued a biscuit and a piece of horse meat per day. We had not seen a bath in four months! There was no water at our positions. There was only a small brook in no-man's land where the both sides drew water. But when the political officers found out, we started pounding on each other. We melted and boiled snow but there must have been something wrong with the snow water - we suffered stomach pains and diarrhea. We were also lice-ridden. We would shake our clothes over red-hot stoves to get rid of the lice. Later, they dropped us underwear that had been treated with Soap K. After some scanty bathing, we put them on and felt as if our bodies were put on fire! This underwear had to be washed all over and only then worn.

- A. D. You must have walked a lot back there.

Well, we did walk a plenty. I think, I must have done at least 300 kilometres during the Finnish War. That would be a very modest estimate. When 44th Division was crushed by the Finns, some of the troops tried to break through, toward the 337th Regiment. I was sent to meet them. When I arrived, I met only several soldiers - the rest had been cut off and slaughtered.

Let's compare, for instance, our skis and the Finnish ones. Our skis didn't have "peksas" - sewn-on toe pockets but had to be tied up with straps. To dismount the skis, one had to untie the straps, to mount - tie them up. Too much hassle. When airplanes dropped valenkis [felt boots] for us, we sewed balls on and slid the foot straight under the arch.

- A. D. How were you dressed?

Our outfits were - greatcoats, budenovka [a helmet-like, cone-shaped canvas cap), leather boots. Lots of weight! Then you have your knapsack, mapholder, revolver, rifle, gas-mask. Why did we carry all that? And it was really, really cold! Both we and the Finns burned bonfires openly - it was much too cold. We got winter camouflage and valenki (felt boots) only when the division was already surrounded near Kuhmoniemi. Our airplanes also dropped winter outfits - black short sheepskin coats for commanding officers. How were we expected to run in attack in the snow, in a black sheepskin coat? Especially, when the battalion commander is leading the attack, 25 metres behind him - the company commander, then - platoon commanders. Of course, the Finns picked out the officers first!

- A. D. What did you think about Finnish soldiers?

Finns make very good fighters and the Great Patriotic War they fought better than the Germans. I see several reasons for that. First, they knew their land and were prepared for this climate. This resulted in minute differences in camouflage, tactics, reconnaissance, all of which eventually bore fruit. Firearms training - excellent. In combat , they are also solid. I noticed, however, that, when they attacked our defense lines, they would make a brisk run for 100-150 metres but then lie down. The Finns are more talkative than even the Germans. The Finnish artillery didn't work that well, but their mortars were good.

- A. D. Were you wounded?

|

I was wounded twice during the Finnish war. The first one was bad. A shell exploded in tree branches and a shrapnel hit me in the left side. We were already running short on medical supplies but we had a great doctor - Captain Sitnikov, who was just saving us. I spent 11 days in the dugout but then again began going out on missions. My light would I got this way. We had a wickerwork strung across a clearing in the woods lest their snipers see our movements. Their mortars were working. I had to go through our pickets and check out the path from our sentry posts to the Finnish lines and beyond. I took two soldiers and took off. Right this minute, the Finns started a mortar bombardment and a projectile hit me in the left hand.

- A. D. What kind of relations did you have with commanding officers? With your subordinates?

We were just friends with my subordinates. There were people of many nations, we lived close and merrily. But we didn't have any relations expressly proscribed by the Service Regulations. The soldiers took care of me. Everything was in the open. Any rowdiness by an officer would end up by his death in the first combat. I have no doubt about that. As far as our command, we had a good relationship with our battalion commander. This was the guy who led us in combat, along with his staff commander and commissar [senior political officer]. We also had good rapport with the regimental officers. On several occasions, I reported to Division Commander Gusevsky, Division Staff Commander Orlyansky, Intelligence Commander Nikiforovich. They paid attention to what I had to say, never interrupted me during the report. I do think that General Gusevsky was a talented officer. Once I reported to Mekhlis who came to Saunoyarvi, the Division headquarters, and spent a night there. Mekhlis left a bad impression on me. He, a very rude person, threatened to execute me if I didn't bring him a prisoner next morning. We spent the whole night on our stomachs - crawling across the lines, the Finns never left their pillboxes. On my return, I reported to the Division Commander and mentioned "That's it, they're going to execute me now." Gusevsky said "Don't worry, he'll come out when you are out there tomorrow you will get him. Don't take unnecessary risks." He reported to Mekhlis and I wasn't called in again.

- A. D. What weapons did you carry?

- I had a rifle and a Nagant revolver.

- A. D. What can you say about the Suomi submachine gun?

- We were on a recon mission once. Our lookout is signaling and I go to him.

- Commander, look, there's something shiny in the snow.

- Everyone pull back! Get me a long stick! - I issue a command.

|

I am thinking, if it goes off - I will die alone. I am pushing it with the stick: It was a cartridge for a Suomi machine carbine. The gun wasn't there. The battalion commander got together all the technical people and Captain Murashkin, Deputy Commander, spent all night treeing to figure out how to load it. He did figure it out and showed us too. We got hold of a Suomi when we took Khiliki 3rd. But we had a very strict order - not to take anything off the dead. Everything had to be turned in! However, when we took defense, then we used them. I fired a Suomi myself. It's a good gun but very heavy. It hangs on your neck like a log. Anyway, the submachine gun's strength is in its impact on the enemy's morale.

- A. D. So you couldn't pick anything foreign?

Yes. I downed a captain under the barbed wire obstacle. We then counterattacked. On the way back, we took his camouflage coveralls off and there we saw a fox furcoat. We took the furcoat off, too. That was when I saw a "Pavel Bure" watch on his wrist. I took it to the battalion commander. None of us had watches back then. The commander slammed at me:

- What did you bring this for?! Now, what if the special department shows up and begins questioning you? Who's gonna do recon? Take everything away!

- They've started cutting the furcoat, - I said.

- What for?

- Soldiers want to sew stockings.

- Okay, let them.

I gave that watch to a sniper. He took them home but the Kem's NKVD (Commissariate of Internal Affairs) took it from him. They were prohibited.

For instance, the Finns had great alcohol-filled compasses. The ones we had - you put it down on something, the needle is still moving. Not with theirs - once it stopped, it stopped. In the nighttime, their entire compass is lit, ours only had a glowing dot on the tip of the needle.

The Finns also had those little sleds (ahkios) which could carry a machine gun, ammunition or the wounded. There were light, lined with thin metal sheets underneath. These sleds glided in the snow like on water! The ahkio had two straps - a long one and a shorter one - to be pulled by two men. We did not have anything like that. Say, somebody gets wounded on a recon mission (and I did have such misfortunes), how carry him back twenty-thirty kilometres in that terrain? Impossible! We make a hundred metres - everybody can barely breathe! Of course, we tried to make some sort of stretchers. But was it ever hard to carry people on them! When we took Finnish ahkios - we weren't allowed to use them. Later on, we began building our own, with wooden box planks, but ours were triangular, with sidings on the edges.

- A. D. Did the Finns have cuckoos (snipers)?

They did. Don't trust anyone who says they didn't - it would be the same as to say that we had submachine guns. I myself took a cuckoo off at 600 metres. And they're lying when saying those were observers, not snipers. They were a real menace for us. We also had snipers - Rochev, Maksimov, Pelekh.

- A. D. Did you have mortars?

|

We didn't have them. Only in the Regiment I saw a 50-mm unit. I think they were useless in the woods.

When, on March 12, the truce came into effect, we received an order to refrain from fire. Only if the Finns attack us. Deputy Battalion Commander Voznesensky was dispatched for negotiations. How to outfit him - all the clothes we had were worn out, torn, burned ! The whole battalion was dressing him up. And we barely managed to outfit him more or less suitably. There were three rounds of negotiations and I was present at the second one. We weren't supposed to take any weapons but I did have a Nagant revolved hidden under my arm. There were three of us and we were met by three Finns. We carried white flags. It was frightening. We stopped. Only 5 metres between us. We began talking through an interpreter. We said that the war is over, a peace agreement signed, we were very happy - it was our victory. There should be no provocations and shooting. We were going to celebrate - play accordions, sing and burn bonfires. The Finns confirmed that the peace agreement was signed and there should be no provocations. In the end, they said "Please do sample our treats." They took off some kind of a cloak of the tray one of the was holding all along and we saw there was sliced fish, meat, I think, pickles and a flask - in which, it turned out, was some sort of berry liqueur. I didn't drink but Voznesensky drank a glass with the Finns. On the first and third rounds I wasn't present but remember they exchanged with knapsacks. In ours, we put some canned food, "Voenny Pokhod" biscuits, and vodka.

When we were leaving, we were ordered to blow up all of our fortifications and fill up the trenches. The Finns were ordered to come off the road for a hundred metres. We sang songs, played accordions. They played harmonicas. I saw them wave hands at us, shake their fists, and we did respond in kind.

As we had been surrounded, I wasn't decorated. They gave me only the "Excellent Serviceman of the RKKA (Red Army)." It was held in respect, though.

What can I say about the Finnish War? Politically - it was a defeat, militarily - a disaster. The Finnish War had a deep impact on us. We saw a lot of grief. We suffered huge losses - which do not even closely compare with theirs. Our dead were left to lie in the foreign land.

Part 2. The Great Patriotic War

Just after the Finnish War I received a battalion under my subordination. At that time the demobilization was declared, and new officers from the reserves arrived in the battalion.

There was a foreboding of a future war. Although the Finnish campaign was considered officially as a victorious one, we, the front-line soldiers and officers, knew its actual worth.

There were learned lessons from the Finnish campaign, and for the period of eighteen months between two wars evident improvements in the Red Army's organization were reached. And the level of its combat readiness was improved. Our troops practiced training in earnest.

The Titovskii UR (Fortified District) had been built on the Murmansk direction2. Three defense lines were set up on the Kandalaksha direction. Another defense line was established on the Sortavala direction.

You couldn't follow the usual way of establishing a defense in a land like Karelia. The outflanking maneuvers of a large military formation were impossible there. So, our defense in Karelia had been realized as covering the main directions - the roads. We made the defense lines along both sides of the road and fortified them with logs and stones. Shortly after the war began the division's defense was disposed in depths but later we made it one-line with a reserve.

Thanks to such a defense the 377th Regiment of our division held the Finns at the border all July long, until we were outflanked and had no choice but retreat.

Nevertheless, all officers of high rank whom I met both during the war and in the postwar times told me that nobody expected the German offensive happened so soon. Therefore many problems were left out. For example, nobody considered the guerilla actions and did not foresee the possibility of cutting off the Kirov railroad. Also the improvement of the control and communication means was almost negligible. Yes, we received two new radio stations; however, the wire and orderlies had held everything up.

My battalion's location was at a distance of 8 kilometers from Kem on the way to Reboly. I knew that, according to the mobilization plan, the battalion's destination is to fight on the Ukhta direction. To reach Ukhta we have to tramp 115 kilometers, and then from Ukhta to the state border 70 kilometers more. And our "wheels" were just horses and our feet. And the feet endured no more than 50 kilometers a day. So, if we reach the border on the fourth day of tramping, - everybody feels back pain and his eyes can't see; and everyone wants to eat, and wants to sleep. And besides, how can we fight in an unfamiliar locality? There you are!

Unfortunately, any kind of preparation for the operations except establishing defensive covers was prohibited in 1941. What did I decide? I went to the head of division's HQ and told him that I had no schemes and no maps and therefore I couldn't estimate the theater of operations. Moreover, I should say openly that our topographical maps of that time were inaccurate.

- No doubt, you remember from the experience of the Finnish War, how many corrections we inserted in the maps at that time, I told him. - I need to reconnoiter that area.

- Keep your desire secret. Don't tell anyone, even your kommissar. Go home and think through what and how you need to do. After you are ready - come again, and we will discuss what to do. (We even hadn't a telephone at that time!)

I decided to organize an outing for officers - a hunting and fishing trip. I issued an order - ": the departure on Saturday at 10 a. m., and the return on 11 p. m.:"

I directed the main group of officers to the fishing trip. The officers of the rear detachments went hunting.

We boarded a truck and made our way toward the border. Frontier guards led us into the 15-kilometer zone, from where we started to go back along the waterway.

I managed to determine all of the bearings up to the 63rd kilometer; we allotted regimental sections; determined the artillery positions and locations of the regimental HQ and services. We also reconnoitered the network of local roads, and looked for trails. Next day the head of the battalion's HQ, Ermilov, did some additional reconnaissance. Then the two together revised our 1: 100 000 map and brought it to the division's HQ. The revised map satisfied the commanders.

The division commander Panin said:

- Noone should know this. You were present at a conference when Antikainen3 made a speech, weren't you?

- Yes, sir!

- Do you feel what is going to happen?!

Antikainen addressed the conference in the clubhouse. While speaking on the Finnish War, he appreciated the formation of both the People's Democratic government of Finland and the Finland People's Army in 1939.

Zelentsov4 told about the aggressive policy of Germany, Turkey, and Japan. In his opinion, a three-party provocation was possible. He also informed us that some German units are in Finland already and a provocation is possible here, too. I will never forget his words: "Your task is watchfulness and combat training. We have to be ready for everything. Let's gather in the harvest - we will see then:" - he cast a sidelong glance at us, then paused. We understood that our offensive would start in fall:

We were preparing for a war. We dug and covered trenches around our barracks. There were permanent exercises: alarms, making bridges, overpassing rivers, setting and clearing minefields etc.

On 22 June we have heard by the radio Molotov's speech about the German aggression. The battle alarm had been declared and straight away we began preparing to leave. The division had to move in the Ukhta direction. There were heard loud oral orders, numerous cries and moans:

According to the plan, my battalion had to follow the 118th Regiment. However when the division commander arrived, he declared that I was appointed the 1st Kem Operational Group Supply Battalion commander. So, I had to stay here and form that battalion and the supply station itself. Then he continued:

- You'll have six companies. Have three of them ready to leave you for combat. Your deputies should prepare the three other companies.

I was shocked:

- Why? I have a war experience! Everyone knows me!

He looked at me:

- I'm wondering about you. Are you a scout, who discusses orders?

What is the Supply Station?

At the beginning of the war the Karelian Front consisted from two formations - the 7th Army and the 14th Army. The supply stations were formed for sorting freight. Each station had one battalion of 1100 men (54 officers among them) and an anti-aircraft company with 12 sets of four machine guns each. The company covered the railroad bridge in Kem.

So, I stayed. Men arrived. The majority of the recruits never touched the trigger! There were no weapons, no uniforms! Nevertheless, we launched the training.

Two companies received and dispatched the freight; they also defended the railroad station. The machine gun company together with two other companies formed the 1st Detached Battalion of the Kem Operational Group.

I was appointed a commander this formation because I was the only professional officer there.

On 1 July the Germans attacked us on the Kandalaksha, Kesting, and Ukhta directions. On 4 July the Finns started their attack on the Reboly direction against the 337th Regiment's troops. My battalion was dispatched to help them. At first we all retreated up to the Rugozero (Rug Lake) where we stopped the enemy. The most terrible fightings were in the Andron Mountain area. We repulsed up to 11 attacks a day! Both sides' losses were substantial. There, during a hand-to-hand fight, I was injured in my eyebrow with a bayonet.

It happened that the Finns crossed a river at our flank. We must not let them farther, otherwise they would grow the bridgehead. And we launched an attack. As we left our foxholes and ran toward the river, the distance between us and the Finns was about 400 meters. The Finns ran towards us, and all gathered in a bayonet fight - the most terrible kind of a fighting!

The combat scattered: now numerous small groups were fighting here and there. I noticed that two Finns were running toward a Soviet soldier. I fired a shot - and one of the two fell down. A moment later I heard some rustling from behind but didn't pay any attention to it and got a rifle butt in the back of my head. I fell down but my rifle still was in my hands. I glanced back - he was ready to stab me with a bayonet attached to his rifle. I managed to evade a direct thrust: his bayonet just slid along my head, and I fired at his belly. In some three minutes my eye had filled with blood - I didn't see anything:

We pushed them out! And we took our former trenches again.

Let me digress for a while. I'm sure that in 1941-1942 a platoon (company, battalion) commander usually didn't survive if they participated in more than three attacks. They were either injured or killed, most likely killed. It was a rare wonder that anyone came through because these officers were going ahead of the attacking wave.

Between August and November 1941 our battalion had lost 12 platoon commanders and 3 company commanders as well as Anna Semenova, our senior nurse. And the commissar was twice injured. (Later, I held a sniper and a machine gunner close to me).

I have seen soldiers shedding tears just before an attack. However, during a combat no one got cold feet. We had no deserters in the battalion as well.

Now I'm going to tell you about my battalion in more detail.

The weaponry. The battalion was armed with rifles, machine guns, hand grenades F-1 and RGD. We also had two sets of four machine guns each; every squad had a machine gun, either the "Degtiarev" or the "Maxim." We didn't have SVTs (Tokarev self-loading rifles) or SMGs. The Finnish "Suomi" was prohibited but sometimes we used them while in periods of defense.

There weren't cannons or mortars in the battalion's structure. Nevertheless, we often had them as an attachment. The 45-mm anti-tank gun was effective. A true powerful rifle! Light, exact. Its piercing ability, however, was not enough to penetrate the tank's armor. At the same time it was a perfect weapon against enemy's infantry and machine gun emplacements. Unfortunately, we have not enough these guns.

The organization of the defense. The localities where we had fought in Karelia were almost impassable; therefore the battalion's sector was no wider than 700 meters. On both flanks sentries were posted. And I put our main body on a zone where the enemy's attack was expected. As a result, our forces were usually concentrated within about 350 meters. There was also a squad, sometimes - a platoon, in the reserve.

The allocation of our machine guns depended on our particular mission. Sometimes I accumulated the squads' machine guns into a group of some 3 to 6 guns and posted it on the most dangerous part of the sector. All our hopes rested upon the group!

Communication means. Because of a small or moderate width of our sector, I mostly used the verbal communication with companies while in attack. Some times, however, I sent an orderly to a company commander. As in a steady defense, we always laid wire. There was also a battalion radio station RBM for communication with HQs.

A typical repulse of an enemy's attack. First of all, as soon as the Finns started their attack I gave a loud drawling command: "At the ene-e-e-my, by a sa-alvo,: fire! By a sa-alvo,: fire!" And the machine guns would also fire. No doubt, after two or three salvos the enemy laid down. At that moment we went in to our counterattack. As it sometimes took place, while in a successful counterattack, you see corpses and injured Finns laying on the land. There were occurrences when a laying soldier fired a burst from his SMG. We finished those off. But others were bandaged and dragged away.

After finishing our counterattack we either started fortifying the captured territory or, if we were short in strength (as it was on the Andron Mountain or, later, - near Medvezhegorsk) we returned to our foxholes.

А. D. - What, in your opinion, were the reasons of our defeats during the first phase of the war?

D. К. - Our sergeants didn't know the character of a combat and were untrained in this respect. The military art was our high ranked officers' the weak spot. And our ranks didn't have any special moral or psychological training. You should teach people to suppress their fear by themselves! For example, a soldier shouldn't lay down during an attack. He must leave his foxhole quickly (in trenches we usually made a couple of steps for that). And must run quickly - it is not a walk to pay a visit. Everyone is shouting hurrah at the beginning of an attack but then turned it into obscene language. As you are in attack - your nerves are very tense. At that moment nobody is thinking about his death!

Let's return to the summer 1941, after some combat came to an end, the division commander ordered me to leave for Petrozavodsk. I boarded three of my companies onto flatcars, and we went to our destination. Since 20 August I was there at the Petrozavodsk force HQ disposal.

They determined for me a boundary line, 12 kilometers from Petrozavodsk, and set me to task building up the first ring of defense of the city. I did it before our forces arrived. Soon after the troops had taken their stands, a fighting began. We held the line for two days without casualties. Then an order arrived: to withdraw. We were brought to Medvezhegorsk. There was the hardest combat there. I was wounded in the knee. Our unit was replaced by another one, and we were brought to Belomorsk.

The war went on at its own pace. In November the 26th Army under Skvirskii's command received fresh forces from Arkhangel'sk and Murmansk. Then our offensive started. We fought the enemy back from Loukh up to Kestinga and made an approach from the North to reach the Sfianga River and then to Kusomo. My battalion's position there was at the left flank (from the road). Then our battalion was shifted back to Kem.

On 20 February 1942, I was summoned to the Kem Operational Group's commander, Nikishov, a clear head. He told me:

- I'd like to have a conversation with you. It is in the nick of time now to change your duties. The Front's reconnaissance department asked me to dispatch you to them.

I didn't want to, I resisted. But Nikishov didn't listen to me. He entered his office and in a minute returned with a Mauser pistol and its certificate in his hands.

- Well, the Order of the Red Banner - is above my level, the Army Commander will award you with it. And I, on behalf of the Kem Operational Group's Council of War, present you, the fighter, with this Mauser.

He invited us to dinner in his office. Everyone filled his glass with vodka, while I poured my glass with wine. In a moment all glasses were emptied to me, the hero of the occasion. (I didn't drink vodka until October 1945. It was my father's order: "Don't drink - otherwise you would be killed! If you'd seize what belongs to others - some gold or silver or even someone's pants - remember: you would be killed! No women, no love, no marriage - otherwise you would be killed! Remember, sonny, during WW-1, only our priests and clerks - we called them 'stallions' in tsar's times - acted like this. They conducted a lot of sexual affairs, they gobbled and drank")

On 23 February I arrived to Belomorsk where I was introduced to Frolov, the Front Commander, to Skvirskii, who was now the Head of the Front HQ, and to Kupriyanov, the head of the Front's Reconnaissance Department. An another life started. I was there the Front 6th Secret-sabotage-service Head, an experienced intelligence officer, Mikhail Il'ich Lapshin's assistant. I held this post from February 1942 till August 1943.

We trained and sent out secret-service men and saboteurs. Yurii Vladimirovich, at that time just Yura, Andropov, the Karelo-Finnish SSR Komsomol Central Committee Secretary, provided us with men for training. After a group was ready, we sent it out or transferred the group to the 1st Branch of the Front's Reconnaissance Department.

The Department consisted of several branches: Secret-service; Army's Reconnaissance; Informational; Connection with guerillas; Sabotage matters. We didn't submit to NKVD but worked in connection with it. NKVD selected the personnel for us. It was Andropov's business.

We trained groups of future agents and after they became completely "ripe," we sent them out. Sometimes in some group there was a special agent whose peculiarity was strongly kept a secret, only the group's commander knew it. At a certain moment the "special agent" disappeared. Then a misleading performance was played to convince all other members of the group that the guy either had been kidnapped as a prisoner for interrogation or he turned out to be a deserter.

In August 1942 we established the 6th Guards Mine-layer Battalion. Its personnel consisted of specially selected soldiers and officers. The battalion had been quartered separately in an out-of-the-way forest near Belomorsk, on the former concentration camp territory, some 20 kilometers from the front line. Nobody knew about its existence.

There were both successes and misfortunes. Once I had to drop off a group of nine agents near Kusomoby at night. The head of the group was "my" former gun crew commander Mel'nikov, a wonderful fighter, a brave and clever man. When our plane was almost approaching the city all hell broke loose: the anti-aircraft fire, searchlights, and pursuit planes. As it was foreseen beforehand, we turned to the secondary target - Nurmis. We dropped them off, however some mistake happened, and they landed almost on the city's outskirts. Moreover, it started dawning. In the early morning they were found out, and the group had no choice but to retreat toward Nurmis. Some Finnish newspaper wrote that they had taken cover in a bathhouse on the outskirts and all were killed. The paper also wrote that someone betrayed the group. I think it is an absolute lie, we had no traitors. (Out of all the sabotage groups I know of only one case when some Kulikov deserted to the enemy in 1944).

In several cases I parachuted along with other agents. After my mission had been fulfilled, I returned on foot. I was met by our trenches. I wore civilian clothes and was unarmed. (To tell you the truth, I did have a small pistol. A comrade-in-arms that gave me it, said: "It's for you." )

Two times I personally was on watch for Captain Patstselo, the Head of the 3rd Branch of Finnish General Staff Secret-sabotage-service. He trained saboteurs, who were recruited among our traitors from Western Fronts. They should perform sabotage actions in Soviet rear.

There is a small village Perunka near Rovanniemi. Patstselo liked to come there almost regularly to take a bath in the local bathhouse. Unfortunately, both my attempts to capture him failed: Patstselo didn't appear these days...

What else did we do? All enemy communications, starting at Lesovodsk up to Rovanniemy, then southward up to Sortavala inclusive, were covered by our reconnaissance net and were under persistent observation.

There wasn't a civilian population in this area. The enemy's transport lines were well stretched out and the reserved troops were situated either in Finland or in Norway. All of these facts were considered and we held the enemy strained. We mined roads, buildings, routes of patrols, bridges (sometimes we blew the latter). We also spread propaganda flyers and started rumors about our imminent offensive. Our activity as well as the Red Army units' activity didn't allow the Finns to take away their troops neither for Moscow nor for Stalingrad or Kursk. They dreaded of losing local rich minerals-fields for iron ore, vanadium, molybdenum, rare metals, diamonds, mica, and construction materials.

The Finns tried to sabotage the Kirov railroad. They sent separate groups of saboteurs a few times. Once such a group actually reached the railroad but the damage they caused was not very sizable:

Shortly before the end of June I unexpectedly left my unit for a completely new battle ground.

Part 3. The War against Japan

At the beginning of preparation for a slashing offensive against the Kvantun Army, some 30 officers, including me, were recalled from the 2nd Belorussian Front. All of them had a good knowledge of transpolar area conditions and were experienced in fighting in forests and mountains.

On 9 July I was in the city of Voroshilov-Ussuriysk already. My first mission was to train three landing parties: for Dankhua, Girin, and Harbin. They were formed on the 20th Assault Field-engineer RGK Brigade's base. I trained the parties in Varfolomeyevka where the 215th Transport Aircraft Regiment was situated. We had a day and night parachute jump training there.

On 9 August, by the Commander's order, I with my soldiers took at night three tunnels near Grodekovo. The Japanese didn't expect our assault. Thus, we opened a 200-kilometers-long route, otherwise the troops would advance through hills.

By 15 August the Japanese were smashed in the border zone, and the Soviet troops were advancing toward central Manchuria sweepingly. The main formation of the Kvantun Army was faced with the fact of complete encirclement. The Japan's government initially tried to maneuver but by 18 August decided to capitulate. To quicken the process of the capitulation, to avert the senseless bloodshed, to avoid destruction of industrial plants and factories, and to lessen the removal or extermination of different goods, our landing parties disembarked at the key locations of enemy's troops and the large-scale cities.

On 18 August Marshal of Soviet Union A. M. Vasilevskii issued a directive to the 1st & 2nd Far-Eastern Fronts and Transbailkalian Front troops: "Because of the fact that the Japanese's' resistance is broken-down and hard road conditions put obstacles in the way of our troops advance, it is necessary to activate specially formed mobile detachments that have to seize the cities Chanchung, Mukden, Girin, and Harbin. These detachments or similar ones should be used for the fulfillment of our next missions without reservations regarding their distant separation from the main forces."

Two landing detachments (commanders Lieutenant Colonel I. N. Zabelin and myself respectively) were ready to fulfil their missions. As early as on 16 August, i. e. before receiving the directive, General Khrenov and I were invited to the 1st Far-Eastern Front Commander, Marshal of Soviet Union K. A. Meretskov. We reported to him the status of our detachments' readiness. The Marshal ordered to direct the detachments to the Khorol airport, where the 281st Transport Aircraft Regiment of the 9th Airborne Army already transferred its base.

From Marshal's office General Khrenov ordered the battalions to gather at the Muchnaya station and Khorol airport by the end of the day. Right away I left for Muchnaya, where the appointed detachments were already situated.

In the morning of 18 August General Khrenov arrived at Khorol airport. He handed me a detailed map of the city Girin with marked objects to be seized and captured: to capture the HQ of Manchou-Go troops and white-guards leaders of the Ataman Semenov's army; to seize the radio station; railroad station; hydroelectric power station; bridges over the Sungari River; military hospital; banks; storage facilities; State institutions; jails; police institutions etc. For communication with the Front HQ we should use the plane's radio station and the mobile radio station "Sever" ("North").

Besides, A. F. Khrenov corrected in my map the numerical strength of my detachment because the 9th Airborne Army was able to provide my first landing group with only seven LI-2 planes.

The General also told me that Colonel Lebedev V. P., the Deputy Chief of the Transbailkalian Front HQ's Operational Department was appointed the representative of the Transbailkalian Front. He will arrive here just before our departure.

Standing near the plane, Major Chetverikov and I made the needed calculations in several minutes. It turned out that in the first flight we can take only 145 members of the detachment itself and 30 specialists of control, armament, communications, foreign languages and medics.

My meeting with Colonel Lebedev took place near the plane, and during the flight we defined more exactly the details of the mission and discussed different versions of the landing party's actions.

That day our landing party couldn't depart for Girin because the situation at that area became complicated: the battered Japan troops still put up resistance. Besides, until evening 18 August, our aerial reconnaissance didn't confirm the existence of a big airdrome there; they saw just a small airstrip. Soon, however, it turned out that the airdrome was well camouflaged. Only at noon on 19 August did our landing group leave for Girin. Four pursuit planes and three PE-2 bombers protected us. Major Chetverikov, the 281st Transport Aircraft Regiment Commander, piloted the leading LI-2. The pursuit planes accompanied us up to the front line, then returned home. The bombers were with us up to Girin. They shook their wings there and left us, too. From then on we'll be alone. Our hearts got sadder.

A small bulb had lashed, and the pilot let us know that the Sungari River would be in seven minutes, we were in 50 kilometers from Girin. All on the plane became more self-disciplined somehow. Everyone was ready to fight to the last cartridge because the help could arrive only by air and no earlier than tomorrow morning.

Our plane steeply dove while penetrating a thick raincloud and downpour. We already saw gleams of the Sungari River, houses, and railway tracks. The aircraft went to come in land but suddenly turned away to the right, then circled again for landing. What was the matter? As it turned out later, the landing strip was very short, moreover, straight toward the strip the pilot saw a few buildings of some factory, and the high factory smokestack complicated the landing. Nevertheless, Major Chetverikov skillfully landed our plane and then dispatched landings of the rest our party's planes.

The weather abruptly took a turn to the worse. The second plane landed, then others. At 18:20 all planes departed for the second echelon of our detachment. Chetverikov's plane was the last, and we hugged one another, while wishing all the best to each other. (At that moment I didn't yet know that I wouldn't see the brave pilot, Major Chetverikov, ever again. As the second echelon approached Girin's area, his plane tragically crashed. All of us were stunned by the Chetverikov's death).

As soon as our first plane taxied to the edge of the airdrome and its engines still continued buzzing, members of the landing detachment started to leap from the plane one after another and ran to several positions around the airdrome that were outlined beforehand. As it was foreseen, our plane temporarily served as my command post.

Soon a Japan soldier and two gendarmes were delivered to me. During a short interrogation they let us know that there was an enemy's ambush on a hill overgrown with gaoliang (sorghum or sorgo).

Colonel Lebedev ordered these Japanese to convey his written note to the commander of the Girin's garrison: "You have to appear at the airdrome along with representatives of the military and civil authorities."

The second our plane with Lieutenant Opriatkin's platoon already landed, the third one was approaching but there wasn't anyone from Japanese yet. An obvious protraction. The tension grew on. The patrols that I sent for seizing cars and trucks didn't return yet as well: Suddenly a bus with the Japan Command's representative arrived. The representative with a white armband on his left arm was accompanied by two escorting officers armed with swords (no firearms was visible). He bowed his head to Lebedev. After a short conversation the Japanese left for their HQ to report about proclaiming the garrison's capitulation.

By that time the Lieutenant Bakhitov's platoon seized and disarmed the airdrome guard. Their armament was bagged, and all of them were directed into the city to their unit.

It was visible that both recently captured Japan gendarmes, who had told us about the ambush, are waiting for something or just dawdled intentionally. And as soon as one of them took out a white handkerchief from his military jacket and waved it, Japanese started intense rifle and machine gun fire from the direction of the hill. We were forced to lie down right near the plane. There wasn't any reaction after my firm request to the gendarme to stop the fire immediately. Therefore Bakhitov's and Gostev's soldiers went in to the attack. In a short but fierce fight they smashed a Japanese company. Eight Hotchkiss machine guns were taken; 80 soldiers and two officers were captured. A lot of enemies were chopped there. To tell you the truth, we tried not to take prisoners. We were angry to the highest degree! There was verbal understanding and they fired at us! On the spot I interrogated the captured company commander. He obviously told lies as declaring that he fought not knowing about the capitulation.

In this fight we suffered five casualties: three soldiers and two officers (Lieutenant Bakhitov and myself) were injured. Bakhitov, who was wounded in the leg, had been taken to our medics. And I in several days found myself in the 110th Military Hospital in the city Voroshilov-Ussuriysk.

Soon three of our platoons drove several captured cars from the airdrome into Girin. There they disarmed the rest of Japan and Manchou-Go detachments. Only in one district they captured 55 soldiers and two officers as well as 10 new American "Studebakers" (we were surprised: why and from where could these trucks appear here?)

Then we seized the Japan HQ office, disarmed its guard and put down the resistance of a few soldiers and officers. In the office we disarmed Lieutenant-General Kuan, Major-General Segu-sin, and another general who was the chief of rear services. While being disarming, they exchanged glances with each other and stated again that they didn't yet receive the order of capitulation from their commander. During the interrogation in then former Japan HQ office, Colonel Lebedev issued our ultimatum for capitulation. He presented our main requirements to the captured generals in a short, insistent but at the same time a correct and polite manner. Beside Colonel Lebedev sat his battle-tried subordinate officers Nikolaev, Gaysenok, Kriukov, Krutskikh and others. A complete set of Soviet Command's terms of the capitulation was dictated to the Japanese. After this General Kuan ordered all their troops to capitulate.

Colonel Lebedev allowed three Japan generals to keep carrying their swords. They took his courtesy with sincere gratitude. Lieutenant-General Kuan and the chief of his HQ, Major-General Segu-sin, showed us on the map where their garrisons were located. Right away we started to accept their capitulation. This day, 19 August, and the next night our groups literally rushed through the city like a whirlwind. They occupied the most important institutions of the garrison. The central offices of the post, telegraph, and telephone were seized as well as banks, hospitals, jails, and brothels. More important objects were captured and put under our guard: the bridges over the Sungari River; the railroad station; the main arsenal; gendarme and police administrations; the military college, several HQs (and banners of specific units there). Among others an Ataman Semenov administration's card index of personal register was found.

A group entered the Manchou-Go commandant's office, where the HQs of the Manchou-Go corps and of the 5th Infantry Brigade were situated. Also some 3000 bandits, as we called them at that time, of the Ataman Semenov's Army were taken prisoner.

The head of one group, sergeant Shvedov, junior sergeant Mikhaelian, soldiers Patrakhin, Raspopov, Chikirzov, and Rasiakulov disarmed entire Japan battalions and put them under guard in their barracks. In some places separate groups of Japanese tried to put up resistance or hide themselves from us. In the Railroad Administration they disguised themselves as civilians and tried to run, then began firing with rifles. Right off our SMG put down their attempt.

We also executed a night mission to seize the hydroelectric power station on the Sungari River. It was located in some 35 kilometers to the northeast from Girin. The length of its dam was 100 meters, the height - 96 meters, and the backwater - 76 meters. Later we got to know that the dam was prepared to be blown up. Chinese engineers told us that if the explosion occurs, the city would be flooded by a huge surge for several minutes.

A field engineering battalion and a separate chemical company guarded the dam. They had here a chain of defensive installations along with centralized smoke-screen sources. Under the cover of night I led two of our platoons to the station and after a roundabout maneuver we surprised the guard of enemy's barracks. The Japanese had no time to organize a defense. We disarmed them and directed to the Girin's barracks.

For this successful mission I was awarded with Kutuzov Order.

The disarmament and acceptance of capitulated troops took place rapidly. By 12:00 20 August 12 000 Japan soldiers were isolated in their barracks and placed under guard. We used many Russian emigrants as interpreters (Russian community in Girin amounted more than 3 500 people).

The Japanese feared going into streets because of the Chinese people's tremendous hatred against them. Time and again crowds of Chinese visited our commandant's office with request to give up the Japanese to them for savage punishment of the occupiers.

At 19:00 19 August the local broadcast announced that a powerful Soviet landing party deposed the Japan rule and the Manchou-Go regime. Also, a decree of the first Soviet Commandant of the city of Girin was proclaimed. There was an offer to create together with the Chinese People's Revolutionary Army a people's authority. All city dwellers were asked to help maintain order.

Different restrictions that had been established by Japanese were canceled. All brothels were closed down. Hundreds of prisoners who had been arrested for their political convictions or for debts to landowners and pawnbrokers were released from custody.

The immediate release was ordered of all convicts from the open street holes where they had been buried up to the neck as well as from the "debtor's holes."

Spontaneous gatherings and meetings took place in the city, Soviet red banners and China's banners fluttered everywhere. It was a bright demonstration of the Soviet-Chinese friendship. Very impressive was the meeting at the local stadium. More than seven thousands Chinese greeted the arrival of the Red Army in the city and in the country.

During days that followed, the people's committees of different level were established. They offered us their services. For example, their activists willingly and diligently carried out both the patrolling and guarding services at most important places such as Japanese prisoners' camps and jails where the traitors the Chinese people; Japan gendarmes and policemen; pawnbrokers and brothels' owners were held.

Everywhere you could hear brisk talks and understandable words Chiso! Shango! (Good! Russians!) The "gesture language" was a wonderful means in realizing the human contacts between Chinese and Russians. For some strange reason all Chinese took us for Captains (Kapitana Rus!) We should protect some small items such as red star badges from our field caps, shoulder straps, and small red star badges from our new Chinese friends. The Chinese kept asking for those items and just as quickly as they obtained them, they attached these souvenirs to their clothes. Everything Soviet had been instantly snatched away, especially newspapers, books, tablespoons, and mess kits. Girin's dwellers had a lot of questions about Soviet Union, and asked what kind of rule and life awaited them. Many elderly Chinese understood the Russian language and acted as voluntary interpreters. City-dwellers offered their services to our soldiers: barbershops; fruits and vegetables; handmade birds that symbolize friendship and love, as well as red Chinese lanterns, both made of paper. The blackout in the city was canceled. Improvised public markets and small shops began to function.

The Girin's broadcast transmitted thanks to the Red Army for liberation from the Japanese-occupiers. Members of our landing party were the first, who liberated the Chinese from 40-year-long occupation and they were the first, who saw the sincere gratitude of the Girin's people to our army and the Soviet people.

Many Girinians visited our HQ which was situated in the former governor's building. Some narrated about their disaster; others asked if they might burn the tax receipts; if it is possible to take away their land from the pawnbrokers, or their cattle and other property. They thanked our army for the liberation; asked us to help both the victims and those, who were living in a state of extreme poverty.

Some members of the landing party were assigned guard commanders to oversee patrolling and guarding the city. In this service numerous citizens, who were specially selected by the People's Committee (the institution of local governing) took part. We armed these activists. It should be noted that these people performed their duties very responsibly, with pride and bravery. They helped to keep the city in a good order and to guard the mass of Japanese prisoners securely. There were many young people among them.

At night 23 August our group, according to the Front's HQ order, "handed over" the seized arsenal to revolutionary formations in Manchuria. That would be an important contribution to the Chinese people's victory in the following years.

There were interesting details of how the removal of armaments, explosives and other property from six huge depots was organized. I was ordered to have no contacts with Chinese People's Army's representatives and also to withdraw our guards from these depots at 1:00 a. m. From then on we should secretly watch how the Chinese remove armament from one of the depots at night.

The removal of the armament was carried out at a brisk pace in a full silence and with a lot of flashlights. Everybody acted as a runner. People carried out most of the armaments alone, in pairs or four together; trucks removed heavy loads. Later, when I inspected the empty depot, there was perfectly swept there and cleanliness reigned everywhere. Even shelves disappeared from the room. The Front HQ thanked us for our perfectly organized handing over of this depot to Chinese.

A private first class, Aslanov, who was awarded with Orders three times, raised the red banner over the former HQ of Manchou-Go troops building, now our HQ and commandant's office. It was visible from far in the city. And right away Chinese were moving there one after the other with their complaints and requests; some wished us all the best or offered their friendly service.

The 1st Far-Eastern Front Commander, Marshal of Soviet Union K. A. Meretskov and the Member of the Council of War Colonel-General T. F. Istokov visited Girin on 23 August.

The Marshal thanked us for a praiseworthy accomplishment of our combat mission and ordered me to recommend the members of the landing party for government awards.

Next day I left for the military hospital.

| Interview: | Artem Drabkin |

| Translated by: | Alexei Gostevskikh and Isaak Kobylyanskiy |

| Proofreading: | Todd Marvin |